Q: What was it like to be an immigrant, and start over in a new country?

Litman:Â The Last Chicken in America was about the initial immigrant experience. Immigration is really hard on your ego. Even the simplest conversation is hard. My English was barely serviceable, but it was the best in the family, so I had to make appointments and ask directions. Your whole sense of self and identity changes. It was incredibly hard on my parents. It felt like everything was breaking apart in various ways. Nothing felt normal.

Q: After college, you worked a number of IT jobs, in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and Boston. Were you also doing creative writing on the side?

Litman:Â Not at first, but I started taking writing classes at night at Cambridge Adult Education and then GrubStreet [a 20-year-old Boston-based creative writing center]. Julie Rold [a fiction writer and liberal arts professor at the Berklee School of Music] was the first person to say I had real talent. It was one of those moments that changes everything.

But writing was always a spare-time thing. I thought that maybe, if I got lucky, I could write part-time and do computer work part-time ”” but the value of what I was doing was edging out the computer stuff. And I was getting a lot of encouragement from teachers like Steve Almond [author of 10 books, including 2014’s Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto]. He’s wonderful. And so I decided to give myself a few years to really work on writing, and I applied to graduate programs.

Q: You attended the MFA program in creative writing at Syracuse University, studying with such luminaries as Gary Lutz, the poet and short story writer; and George Saunders, the MacArthur “Genius” Award winner and author of this year’s acclaimed Lincoln in the Bardo. How was that experience?

Litman: I got incredibly lucky! George Saunders became my thesis advisor, and he was generous to me, and to all his students. I learned a ton from his literature classes, and I learned how to teach creative writing classes too. He had a very intuitive approach to responding to students’ work, and to the energy of a class. He always talked about having respect for the reader. Think of your writing as if you’re driving a motorcycle, he’d say, and the reader is in the sidecar right next to you. You don’t want to condescend. The reader is an equal.

Half of us were doing traditional writing, half were more experimental. I’m more traditional. Gary Lutz approached language like a poet would. And the teachers all offered gentle encouragement if something could be improved in your writing, if each word was the best possible choice. I wrote the bulk of the stories for Last Chicken at Syracuse, and had the manuscript by the time I finished.

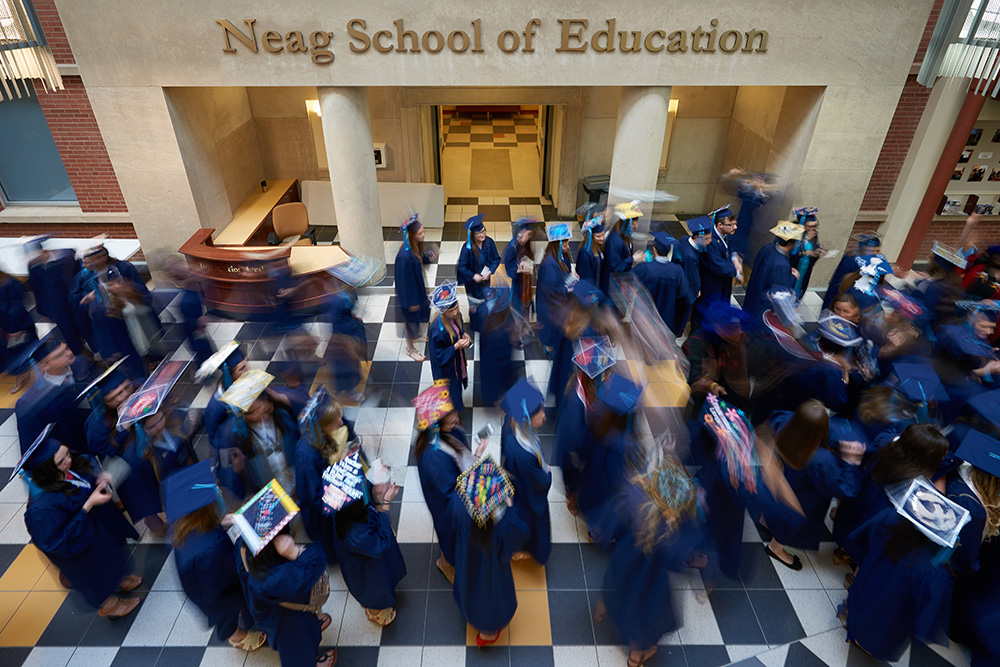

Q: How did you end up at UConn?

Litman: After I taught some workshops at Syracuse, I taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and also at Babson College in Wellesley, Massachusetts. After Norton published Last Chicken in America, I thought I’d see where it took me. The poet Penelope Pelizzon [associate professor, Department of English] was on the search committee at UConn. She was the one who really loved the book. She’s been my champion and mentor and supporter ever since. We went on to co-direct the Creative Writing Program in the English Department. It’s a really great program. It’s not a big program, but it’s found a lot of people whose work I admire.

I started here in 2007, before I had kids. And then when I had kids (Polina, 7, and Olwen, 3), I have found it to be a really supportive family-friendly environment. I love this place.

Q: Speaking of family, let me mention your husband, Ian Fraser. He’s a native of Johannesburg, South Africa, and was a playwright, fiction writer, and standup comedian there. How did you two meet?

Litman: On the T! We were on the Red Line in Boston. We both got on at Park Street and got off at Harvard Square. He was visiting America and asked if he was on the right platform, which started a conversation, and he asked if I’d like to go out on a coffee date. I said yes.

He left for home the next day, but we emailed and Skyped, met in London, and were married six months later.

Q: In the book, Kat’s parents are dissidents. Were your parents dissidents, too?

Litman: No. My parents were part of a generation that had experienced many hard things, and they did not want to be involved. They were very cautious and needed to be cautious. It was ingrained in me, too, to be cautious.

But I did have these two charismatic literature teachers in my life, who I just adored. Anechka and Misha [Kat’s parents in the book] were a product of that. But once I had these characters, I couldn’t rely on my own experience so much. I was more well-behaved than Kat. My eldest daughter is very self-confident and will debate her teacher and ask for help. And I’m this mouse!

Part of it is that my daughter’s a product of where she was born, and I’m still a product of where I was born. In Russia, in my brace, I had to brace myself. I was pointed at. And anyone, at any time, a neighbor, a clerk, will yell at you for no good reason. In my day, rudeness was just part of the reality in Russia. Everything is state-run. There was no competition. Why be nice? It’s not like you’ll go to a different store.

Q: What are you working on now?

Litman: I’m in the middle of three different projects. One is a sequel to Mannequin Girl, with some of the same characters, set in the late perestroika years. Having lived with perestroika, I’m very much interested in how it shaped one’s political sensibilities.

But of course, corruption set in after perestroika, and eventually this led the way to Putin. In America, people may believe in a leader. I don’t think many Russians have that idealism.

In my Immigrant Narrative class now, we talk about how America is supposed to be the land of immigrants. But it’s never been equally accepting to immigrants, letting in European immigrants but not Asian immigrants in the past, for instance. My students can find this a revelation. With what’s going on in the news with immigration, every day, it all completely resonates with them now. And with me.