Hans Rhynhart ’93 (CAHNR)

Hans Rhynhart ’93 (CAHNR)

With a slight crane of the neck, peering from the corner of UConn Police Chief Hans Rhynhart’s second-floor office window affords a sliver of a view of an empty lot atop King Hill Road, bounded by vegetation and parking spots.

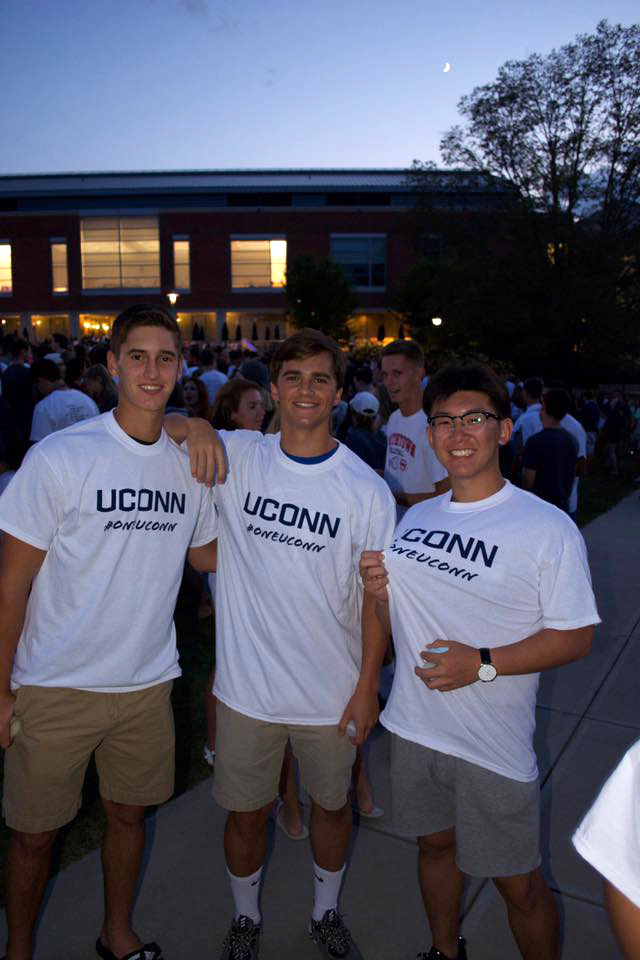

Generations of UConn students came and went over the decades as renters in a two-story red house that once stood ”” or, some would say, tottered ”” on that lot. Its unbeatable location and the warmth of roommate friendships easily compensated for its grungy floors, bare-bones kitchen, and the broken door, whose missing lock allowed genial strangers to wander in for a bathroom break after closing time at the nearby bars.

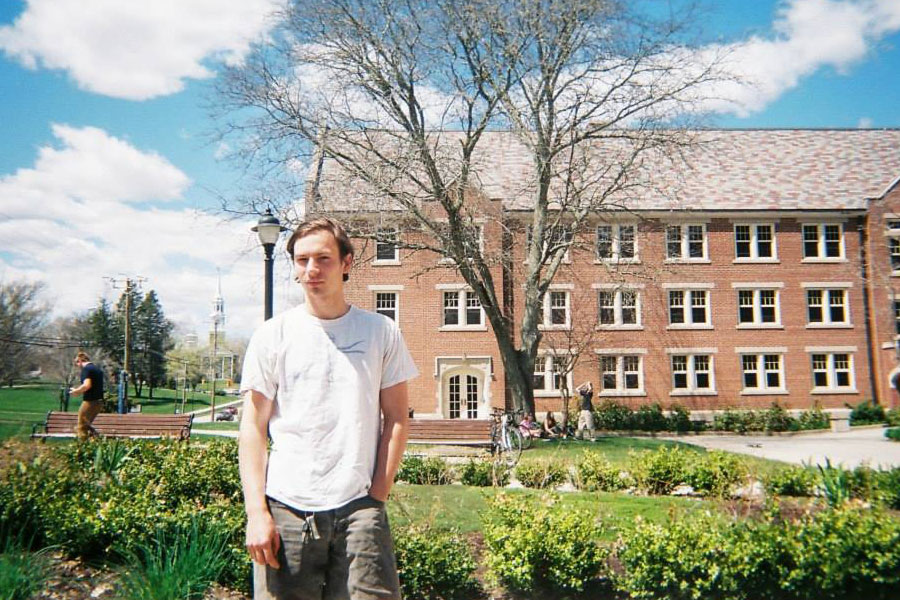

Among those renters: Rhynhart, a quiet but companionable undergrad whose engineering aspirations had given way to an interest in natural resources management. He never imagined that more than two decades later, his admiration for law enforcement would lead him to the top spot at the UConn Police Department, which he’d walked past regularly as a student heading to and from his modest digs.

Rhynhart ’93 (CAHNR) was named to UConn’s top police job in January after serving in the interim role for seven months. He is also interim director of public safety, a position in which he also oversees the UConn Fire Department, Office of Emergency Management, and the Fire Marshal & Building Inspector’s Office.

“Coming to UConn has been one of the best returns on investment I’ve ever made in terms of the education I received as a student and the opportunities I’ve been able to pursue in the police department,” Rhynhart says.

In the dorms

A Woodstock native, Rhynhart spent his freshman year at Johnson State College in Vermont before transferring to UConn and moving into Goodyear Hall, where some of his closest friendships were forged over the family-style dinners that were served there before meals were consolidated into the Northwest complex’s main dining hall.

Bryan Busch ’93 (ENG), ’98 MS, who remains one of his close friends, says the Hans who wears the chief’s badge today is the same earnest and honest person he met at Goodyear and with whom he later roomed in New London Hall and that memorable red house on King Hill Road.

“The best way I can describe Hans is that he’s a stand-up guy. He has your back as a friend, and he has integrity in his work and his life,” Busch says.

Part of that work included several summers with the agency now known as the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. That’s where his respect for law enforcement transformed into admiration ”” and the start of a career aspiration ”” as he worked closely with officers in the state’s Environmental Conservation (EnCon) Police.

Rhynhart worked as an environmental analyst in Vermont and Connecticut after college until 1998, when he decided to pursue his law enforcement ambitions. He was hired at the Department of Motor Vehicles and went through the Connecticut Police Academy, working as a vehicle safety inspector until he applied for a UConn police job at the encouragement of a DMV supervisor who recognized his potential.

From his first few days on the job in June 2001, the UConn Police Department has felt like home.

Undercover

Rhynhart’s familiarity with the campuses and the ease with which he interacts with others has benefited UConn time and time again ”” including a 2002 undercover stint when he posed as a graduate student as part of a team of officers who apprehended 13 people who were using and selling heroin and other drugs on campus.

Rhynhart was so laid back that the students he was investigating assumed he was an amiable stoner and welcomed him into their fold ”” and to this day, colleagues never tire of teasing him about the long hair, scraggly goatee, and ratty clothes that made him appear so convincing, even as he counted down the days until a return to his clean-cut self.

Unruffled

His talent helped him move quickly up the ranks over the coming years, earning him a spot in the FBI National Academy professional development program in Quantico, Virginia, in 2009, and he eventually became second in command at the police department in 2011. He later was appointed deputy chief, and held that job until his interim appointment as chief in May 2016.

“The people I’ve worked for at UConn have always looked toward the future and considered how to bring people along to cultivate the next generation of leaders. I consider that to be a very important part of this job, too,” Rhynhart says.

He jokes in his self-deprecating style that he’s not the best at anything ”” not the best shooter in the department, not the fastest runner, he says ”” but, “if there’s one thing I believe I am good at, it’s putting people in the right positions to succeed, not only for themselves but also for the organization and the community we serve.”

Even through the hardest days ”” notifying parents of their children’s unexpected deaths, manning the front lines during Spring Weekends, training to guard against acts of terrorism ”” Rhynhart is consistently calm, rational, and unfailingly reliable in the eyes of those who depend on him and his public safety personnel for the safety of the campuses.

“Police work on a college campus requires a special set of skills and sensitivity, and Hans has always had the ability to build those kinds of trusting relationships throughout the UConn community,” President Susan Herbst says. “His UConn roots run deep, and we’re incredibly fortunate and grateful to have him here.”

Several people who work with Rhynhart say that even in the midst of stressful situations, his demeanor is calm and authoritative. He jokes that he is like the proverbial duck who appears placid on the surface while paddling madly out of sight below the water ”” but it’s his gravitas that stays with those who meet him.

“Even as a student in my classes, he was steady and he had a presence. He stood out as a solid individual, and that is the same kind of person he is today,” says John “Jack” Clausen, a professor in the UConn Department of Natural Resources and the Environment.

“At one point when he was the police department’s spokesperson, I saw him on TV one night and said, ”˜Oh, wow, he’s doing an amazing job ”” he’s so composed and well spoken.’ At that particular moment, I had a feeling of pride that he came through our program.”

All Blue

Those who know Rhynhart say that off duty, you’re most likely to find him spending time with his 15-year-old daughter Emma, 13-year-old son Hans, and his wife, first-grade teacher Beth (Swenson) Rhynhart ”˜95 (CLAS), who he met in the Homer Babbidge Library when both were UConn students. He’s also likely to be working on renovations to their 1840s-era house or barn, or tinkering with an engine, or seeking out bargains to appease his frugal nature.

He certainly won’t be idle.

In fact, these days, you’re certain to find him with textbooks and meticulous notes from the classes he’s taking to earn his master’s degree in human resource management at the UConn School of Business. Like his other endeavors, he’s jumped in wholeheartedly.

“Being a student again, I’m taking it all in like a sponge,” he says.

And while he’s come a long way from his undergraduate days in that ramshackle red house on King Hill Road, Rhynhart is still the person who impressed his professors with his maturity, cultivated countless friends with his sincerity, and jumped at the chance to serve the alma mater he loves.

“UConn has given me a chance to be part of something that makes a positive difference and has lasting meaning,” Rhynhart says. “The police department and the UConn community as a whole fit really well with who I am as a person, and I’m grateful for the opportunities I have here.”

””stephanie reitz