August 14, 2017

A Total Eclipse of the Heart (of America)

A spectacular and likely unforgettable show will take place in the sky Aug. 21.

“Have you ever seen a total solar eclipse?” asks Cynthia Peterson, professor emerita of physics. “It’s a really, really exciting event!”

The reason she and so many others are excited for this event has a lot to do with its rarity. The last time a total solar eclipse was visible from the mainland United States was 38 years ago, in February 1979.

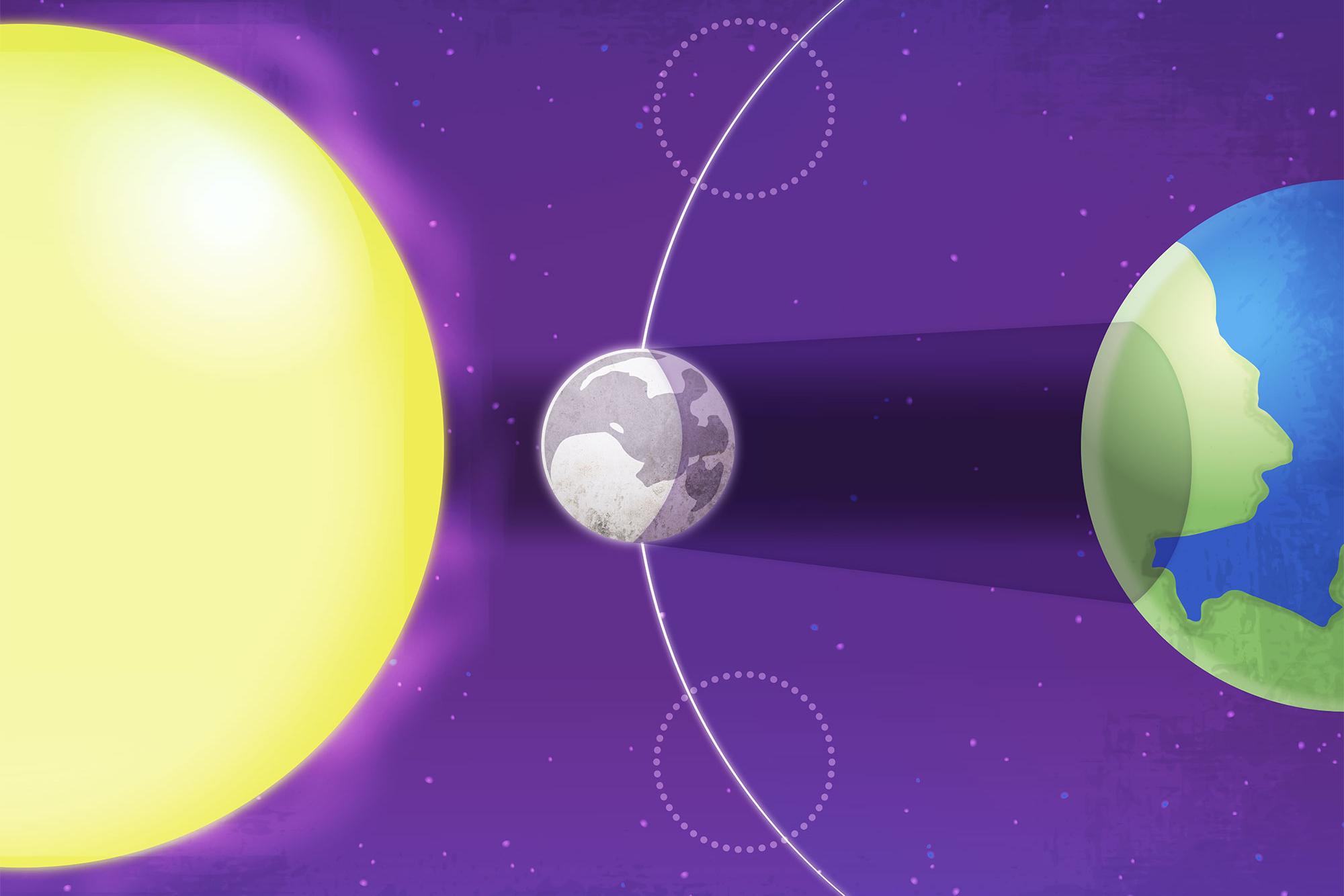

Very specific conditions have to be met to create an eclipse that can be viewed from Earth. The Earth and the moon must align perfectly with the sun as they speed through space, an amazing coincidence. To fully understand how this happens, Peterson says, it’s helpful to know some basic astronomy.

Conditions for a Total Solar Eclipse

The Earth moves in space around the sun, completing a full orbit once every 365.25 days, she explains. As the Earth and other members of our solar system travel around the sun, they continue in essentially the same plane, on a path called the ecliptic. Some celestial bodies, such as our moon, deviate from the ecliptic slightly.

The orbit of the moon is inclined on the ecliptic plane at an inclination of 5 degrees. As the moon deviates 5 degrees above or below the ecliptic plane, it will cross the plane at points called nodes.

“That is the first essential piece of the eclipse puzzle,” says Peterson. “The moon must be at a node for an eclipse to occur. Otherwise, the moon will not align and no eclipse will be seen from Earth.”

The moon’s position in the lunar cycle is another vital eclipse component. As the Earth travels in its orbit, the moon tags along, keeping its gaze locked on Earth, always facing from the same side as it completes its own orbit around Earth once every 29.5 days. Over the course of a month, the moon’s appearance changes, from crescent to full to crescent again and finally to what appears to be its absence, when it’s called a new moon. A new moon is the other requirement for a solar eclipse.

“The basic rule for a solar eclipse is to have a new moon at a node,” Peterson points out.

But during an eclipse, how can our moon, which is relatively small, appear almost as big as the sun, which is pretty gigantic?

Peterson explains, “The sun is 400 times bigger than the moon and the sun is also 400 times farther away from the moon, so the moon appears to fit exactly during an eclipse, when they are both the same angular size.”

Holding up her fist, she demonstrates: “Find a large object ahead of you and pretend it is the sun and your fist is the moon. If you hold up your fist and look with one eye, you can’t see the object/sun.”

These are the conditions for a total solar eclipse like the one coming up. “Solar eclipses happen when the new moon obstructs the sun and the moon’s shadow falls on the earth, creating a total solar eclipse.” Peterson moves her fist slightly away from herself until the edges of the object can be seen around it. “Or, when the moon covers the Sun’s center and creates a ”˜ring of fire’ around the moon, it’s what’s called an annular eclipse.”