PHAR 1001: Toxic Chemicals and Health

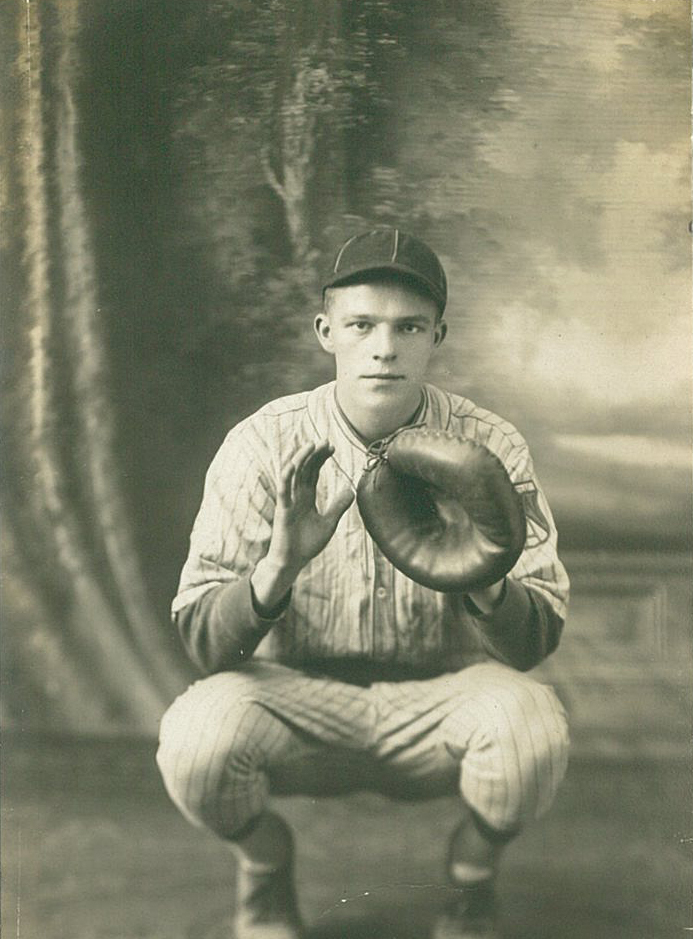

David Grant at Shamrock Tattoo Company in West Hartford, Conn. One of his most popular lectures is on the toxic heavy metals in tattoo ink.

The Instructor:

“Everything is toxic,” David Grant likes to tell students early on in his time with them. He will say it matter-of-factly and then pause, contentedly watching the wheels turn with the processing of unexpected and perhaps unsettling information.

As a mind-bending example, Grant, professor of pharmacology and toxicology in the School of Pharmacy, cites a hazing incident at a California university a decade ago in which a fraternity pledge was forced to drink a massive amount of water. This triggered hyponatremia, an abnormal drop in the body’s sodium level. The student died from too much water.

“It’s all about the dose,” says Grant, who loves hitting his students with surprising answers. He uses iClickers so students can answer his questions by clicking in, game show style, and the congregate answers appear on a board at the front. Much of the time, their assumptions prove widely held ”” and wrong.

Often it’s due to the all-about-the-dose maxim, which holds true, Grant points out, when it comes to many substances we generally think of as toxic. Cancer rates spike among populations exposed to radiation from a nuclear reactor meltdown, for instance, but one can undergo an X-ray without a significant health risk. “If I smoke a cigarette once in my life, it’s not going to hurt me,” he says. “Smoke two packs a day, that’s a different issue. Everything will kill you if you take in too much of it. Everything.”

Class Description:

Toxic Chemicals and Health is a freshman-level lecture course that addresses the risks to human health posed by exposure to various chemicals.

Most of his teaching is with upper-class science majors, so Grant was excited when the opportunity came to teach this introductory course for nonscientists. A good many of the university’s athletes enroll, and Grant finds they often are among the best students in the class. “That makes sense to me,” he says, “because high-level athletes tend to be interested in understanding their body’s interactions with supplements and substances that enhance athletic performance.” For one lecture, Grant brings in an emergency room physician who also happens to be a triathlete.

Grant’s Teaching Style:

In the Toxic Chemicals and Health classroom, Grant says he’s been learning as much as teaching ”” learning, that is, what can be toxic to a large lecture environment. After spending two semesters trying to hold the interest of 175 students, he’s decided to no longer allow open laptops.

“It’s not just that I’m annoyed when students are paying attention to something else,” he says. “I’ve done some research, and several publications support the idea that people are distracted by multitasking.” Grant believes there’s also a benefit in taking notes longhand, “because you cannot simply type everything the instructor is saying ”” you have to summarize, which helps you learn. It’s been scientifically shown.”

But don’t confuse Grant for a technophobe. His students all use the high-tech iClicker. With one of those devices in the hand of each student, and a wireless receiver on the podium beside him, Grant can make real-time assessments of how well his lectures and other class materials are being received.

“I can get a sense whether they’re understanding the concepts,” he says, “or even paying attention.”

Grant also invites students to text him with questions during the break halfway through the 75-minute lecture. He addresses some of those questions in the second half of class. “I’ve told other faculty I do this,” he says, “and they look at me, like, ”˜Are you crazy?’” However, any fears that he’ll be flooded with texts at all times have not come to be. For Grant, the texting option simply casts a wider net for student questions. “Those who are hesitant to speak up in class, for fear of looking stupid,” he says, “now get their questions answered.”

When and Where:

The course is taught each spring in Storrs.

Why We Want to Take It Ourselves:

“Bioterrorism agents,” Grant says brightly. He’s just been asked what topics are most popular with students, and this is the first thing to come to mind.

That may not be the most uplifting conversation piece, but it’s certainly a concern for many in today’s world, and Grant keeps Toxic Chemicals and Health fresh by shaping lectures around current issues. In a talk about food additives, for example, he delves into organic food ”” the science and the media hype. “It turns out there’s no nutritional difference between organic foods and conventional foods,” he says. That there’s an unquestioned fear of chemical additives among health food shoppers, says Grant, points to our culture’s shaky relationship with science. “We look for evidence to support our beliefs, and we find it, because there’s so much out there,” he says. “But we don’t look beyond what we want to find.”

This year, for the first time, Grant will address the use of animals in scientific research. “A lot of people think scientists abuse animals,” he says. “So we’ll talk about how we are allowed to utilize animals ”” how the process works, and how we have to guarantee humane treatment.”

When discussing environmental pollution, Grant cites the dredging project under way on the Hudson River in New York and the infamously lead-contaminated drinking water in Flint, Michigan.

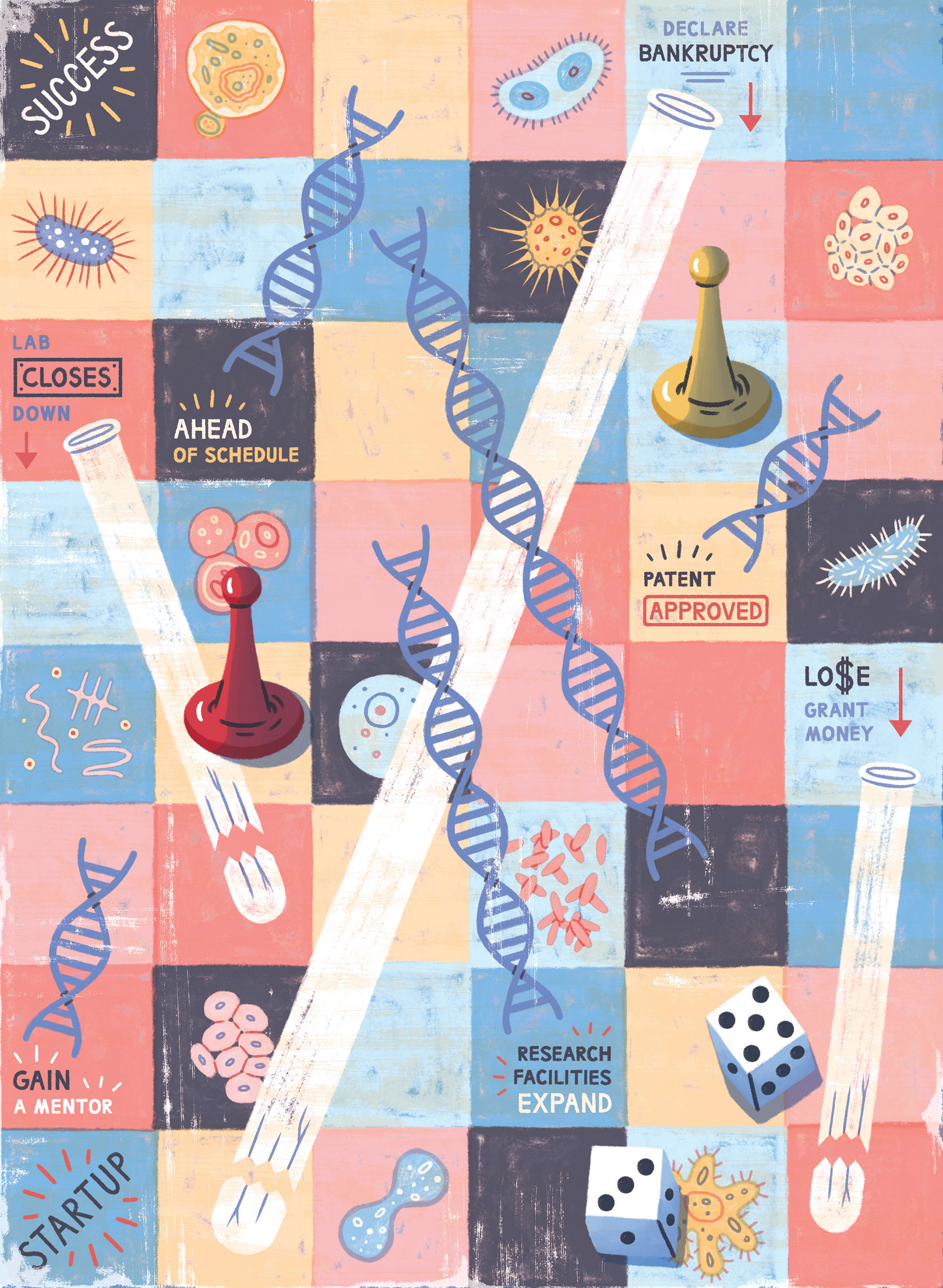

Another topic that hits home for students today is his tattoo lecture. Some tattoo inks, Grant points out, contain relatively high concentrations of heavy metals that are known toxins. So he asks: Does that make tattoos dangerous?

Once again, the answer doesn’t align with what a student might have heard from his or her mother after casually mentioning at family dinner an intention to get a tat.

“You’re getting such a small amount of toxic material,” says Grant, “it doesn’t matter, probably.” Probably?

“Well, it’s very hard to determine cause and effect, with so many variables,” says Grant. The concentration of toxins in tattoo ink will vary, as will the size and internal makeup of people being inked up. “So we just don’t know for sure,” he says. “And I know that ”˜we don’t know’ is an answer that can cause some angst. But it’s honest, and that’s what I want students to take away from this class.”

””JEFF WAGENHEIM