Class Notes

Share your news with UConn Nation!

Your classmates want to know about ”” and see ”” the milestones in your life. Send us news about weddings, births, new jobs, new publications, and more ”” along with hi-res photos ”” to: Alumni News & Notes, UConn Foundation, 2384 Alumni Drive, Unit 3053, Storrs, CT 06269.

Submissions may be edited for clarity or length.

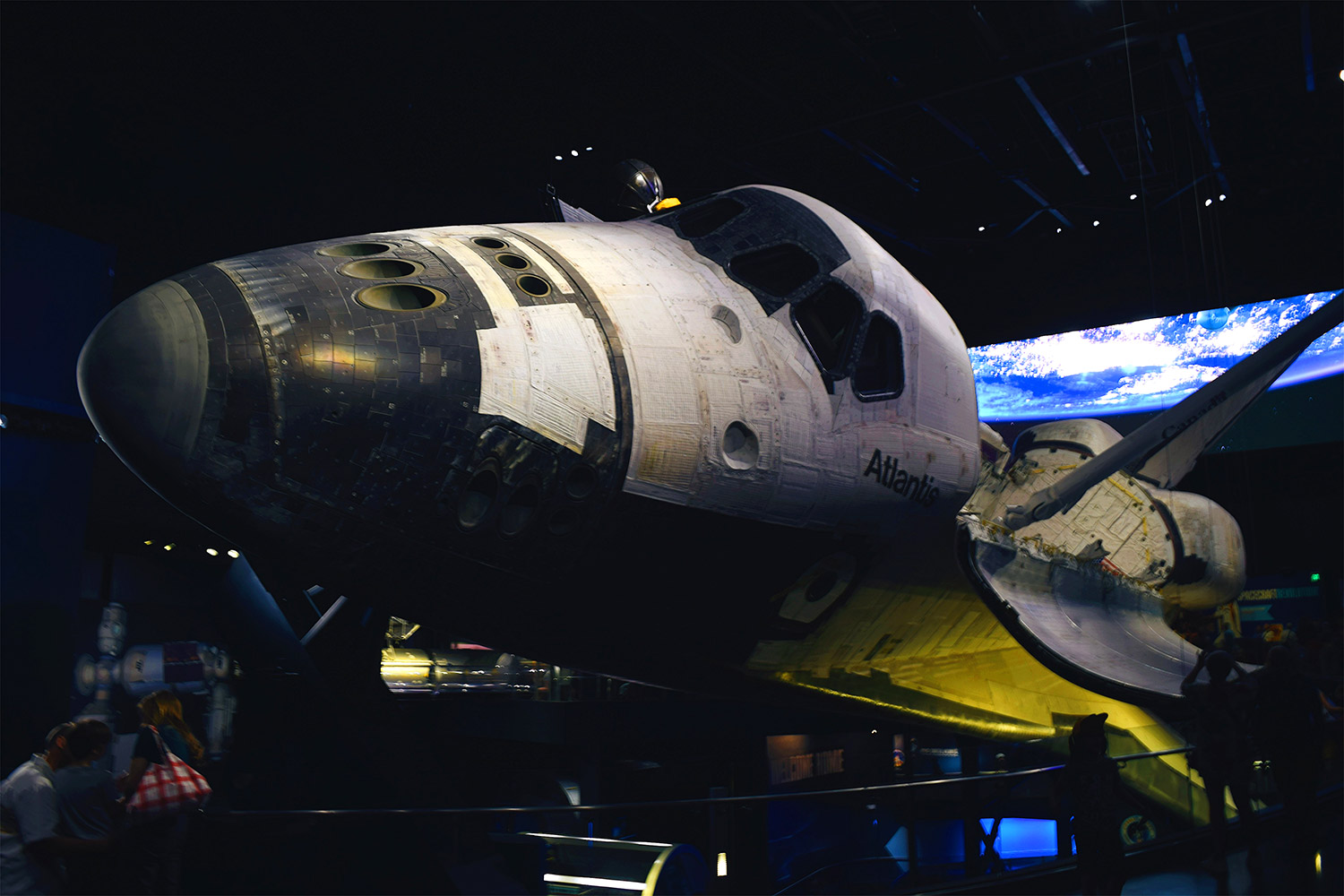

![]() Â Roland Boucher ’54 (ENG), who bought his first plane in 1952 when he was still a sophomore at UConn, reports that he is still flying and is now a retired engineering manager in Irvine, Calif. After college, he earned a master’s degree at Yale University, then worked for Hughes Aircraft Co. in Culver City, Calif., where he designed satellites for communication, navigation, and weather observation. After leaving Hughes in 1973, he obtained a patent for an electric-powered aircraft and developed both the first electric-powered battlefield drone aircraft and the first high-altitude, solar-powered, electric aircraft. A fan of the study of ancient civilizations, he recently presented an article he wrote on the use of the pendulum in the creation of a number of measurements during the Aerospace Systems and Technology Conference.

Roland Boucher ’54 (ENG), who bought his first plane in 1952 when he was still a sophomore at UConn, reports that he is still flying and is now a retired engineering manager in Irvine, Calif. After college, he earned a master’s degree at Yale University, then worked for Hughes Aircraft Co. in Culver City, Calif., where he designed satellites for communication, navigation, and weather observation. After leaving Hughes in 1973, he obtained a patent for an electric-powered aircraft and developed both the first electric-powered battlefield drone aircraft and the first high-altitude, solar-powered, electric aircraft. A fan of the study of ancient civilizations, he recently presented an article he wrote on the use of the pendulum in the creation of a number of measurements during the Aerospace Systems and Technology Conference.

![]() David S. Salsburg ’67 Ph.D., recently released a new book, Errors, Blunders, and Lies: How to Tell the Difference, the first in a planned series on statistical reasoning in science and society, sponsored by the American Statistical Association. Salsburg shares that upon graduation, “I was the first statistician hired by Pfizer, Inc., and was involved in the development of new drugs for almost 30 years. Before that, I taught at the University of Pennsylvania and, while at Pfizer, taught courses at the University of Connecticut and Connecticut College. Since retiring, I have taught at the Harvard School of Public Health and have been an adjunct professor at Yale. My book on the history of statistics, The Lady Tasting Tea: How Statistics Revolutionized Science in the Twentieth Century, has been widely used as a supplemental text in high school and college statistics courses.”

David S. Salsburg ’67 Ph.D., recently released a new book, Errors, Blunders, and Lies: How to Tell the Difference, the first in a planned series on statistical reasoning in science and society, sponsored by the American Statistical Association. Salsburg shares that upon graduation, “I was the first statistician hired by Pfizer, Inc., and was involved in the development of new drugs for almost 30 years. Before that, I taught at the University of Pennsylvania and, while at Pfizer, taught courses at the University of Connecticut and Connecticut College. Since retiring, I have taught at the Harvard School of Public Health and have been an adjunct professor at Yale. My book on the history of statistics, The Lady Tasting Tea: How Statistics Revolutionized Science in the Twentieth Century, has been widely used as a supplemental text in high school and college statistics courses.”

![]() Perry Zirkel ’68 MA, ’72 Ph.D., ’76 JD, professor emeritus of education and law at Lehigh University, was honored with the 2016 Steven S. Goldberg Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Education Law, given by the Education Law Association. Zirkel’s research currently focuses on empirical and practical studies of special education law, with secondary attention to more general education law and labor arbitration issues.

Perry Zirkel ’68 MA, ’72 Ph.D., ’76 JD, professor emeritus of education and law at Lehigh University, was honored with the 2016 Steven S. Goldberg Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Education Law, given by the Education Law Association. Zirkel’s research currently focuses on empirical and practical studies of special education law, with secondary attention to more general education law and labor arbitration issues.

![]() Bill DeWalt ’69 (CLAS), ’76 Ph.D. was named chair of board of trustees of the Pennsylvania chapter of the Nature Conservancy. During his long and distinguished academic career, DeWalt authored or coauthored many books and articles about the relationship between humans and natural resources, advised many Ph.D. students, and won teaching and research awards at the University of Kentucky and University of Pittsburgh. He served as director of the renowned Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, where he was also Distinguished Service Professor of Public and International Affairs. He then became director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and, in 2007, he was founding president and director of the new $250 million Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. In 2014, he became executive vice president and museum director of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate in Boston. Now retired, he lives in Fox Chapel, Pa.

Bill DeWalt ’69 (CLAS), ’76 Ph.D. was named chair of board of trustees of the Pennsylvania chapter of the Nature Conservancy. During his long and distinguished academic career, DeWalt authored or coauthored many books and articles about the relationship between humans and natural resources, advised many Ph.D. students, and won teaching and research awards at the University of Kentucky and University of Pittsburgh. He served as director of the renowned Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, where he was also Distinguished Service Professor of Public and International Affairs. He then became director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and, in 2007, he was founding president and director of the new $250 million Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. In 2014, he became executive vice president and museum director of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate in Boston. Now retired, he lives in Fox Chapel, Pa.

![]() Ed Nusbaum ’70 (CLAS), of Weston, Conn., has been selected an America’s Top 100 Attorneys Lifetime Achievement member for Connecticut. Less than one-half of a percent of active attorneys in the United States will receive this honor. He is principal and co-founder of Nusbaum & Parrino P.C., a family law firm based in Westport, Conn.

Ed Nusbaum ’70 (CLAS), of Weston, Conn., has been selected an America’s Top 100 Attorneys Lifetime Achievement member for Connecticut. Less than one-half of a percent of active attorneys in the United States will receive this honor. He is principal and co-founder of Nusbaum & Parrino P.C., a family law firm based in Westport, Conn.

![]() Steve Maguire ’75 (CLAS), ’76 MA, has just released a Vietnam War novel, Mekong Meridian. Much of the story is drawn from Maguire’s experience as an Airborne-Ranger Infantry officer with the 9th Division in 1969.

Steve Maguire ’75 (CLAS), ’76 MA, has just released a Vietnam War novel, Mekong Meridian. Much of the story is drawn from Maguire’s experience as an Airborne-Ranger Infantry officer with the 9th Division in 1969.

![]() Tom Morganti ’76 (CAHNR), a veterinarian living and working in Avon, Conn., has just published a first novel, Totenkopf, a thriller set in Germany in the final days of WWII.

Tom Morganti ’76 (CAHNR), a veterinarian living and working in Avon, Conn., has just published a first novel, Totenkopf, a thriller set in Germany in the final days of WWII.

![]() Richard Boch ’76 (CLAS), who was the bouncer at the notorious Mudd Club, a new-wave club in New York’s Greenwich Village during the late ’70s, reports that his memoir on the club was published this summer. The book, The Mudd Club, describes his life two years after graduating from UConn when he lived in Greenwich Village and worked at the door of the famous club with its eclectic core of regulars, including Johnny Rotten, Frank Zappa, Talking Heads, and John Belushi. The ultra-hip club attracted no wave and post-punk artists, along with musicians, filmmakers, and writers.

Richard Boch ’76 (CLAS), who was the bouncer at the notorious Mudd Club, a new-wave club in New York’s Greenwich Village during the late ’70s, reports that his memoir on the club was published this summer. The book, The Mudd Club, describes his life two years after graduating from UConn when he lived in Greenwich Village and worked at the door of the famous club with its eclectic core of regulars, including Johnny Rotten, Frank Zappa, Talking Heads, and John Belushi. The ultra-hip club attracted no wave and post-punk artists, along with musicians, filmmakers, and writers.

![]() Robinson+Cole lawyer Dennis C. Cavanaugh ’78 (CLAS) has been named the Best Lawyers 2017 “Lawyer of the Year” in Connecticut for construction law. He is a member of the firm’s construction group, where he focuses his practice on construction and surety law, including transactional work and litigation. He has more than 35 years of experience handling complex construction matters involving contract procurement, negotiation, financing, and commercial-related dispute resolution and litigation.

Robinson+Cole lawyer Dennis C. Cavanaugh ’78 (CLAS) has been named the Best Lawyers 2017 “Lawyer of the Year” in Connecticut for construction law. He is a member of the firm’s construction group, where he focuses his practice on construction and surety law, including transactional work and litigation. He has more than 35 years of experience handling complex construction matters involving contract procurement, negotiation, financing, and commercial-related dispute resolution and litigation.

![]() Susie Bisulca Beam ’80 (CLAS) wrote a book, He’s Not My Husband, published by Xlibris Publishing.

Susie Bisulca Beam ’80 (CLAS) wrote a book, He’s Not My Husband, published by Xlibris Publishing.

![]() Everyone in the Myers family is a Husky through and through. Peggy (Walsh) Myers ’86 (CLAS) played on the women’s basketball team, and her husband, Norm Myers, 1985 (CLAS), was a football player at UConn. Their daughter, Kelly Myers ’15 (CLAS), who earned her undergraduate degree in psychology and is earning her master’s in school counseling, was on the UConn track and field team. Their son, Tommy Myers ’17 (CLAS), graduated with a communication degree and is currently on the football team. He plans to earn his master’s in sports management.

Everyone in the Myers family is a Husky through and through. Peggy (Walsh) Myers ’86 (CLAS) played on the women’s basketball team, and her husband, Norm Myers, 1985 (CLAS), was a football player at UConn. Their daughter, Kelly Myers ’15 (CLAS), who earned her undergraduate degree in psychology and is earning her master’s in school counseling, was on the UConn track and field team. Their son, Tommy Myers ’17 (CLAS), graduated with a communication degree and is currently on the football team. He plans to earn his master’s in sports management.

![]() Pamela Hackbart-Dean ’87 MA, director of the Special Collections Research Center at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, was inducted as a Fellow of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) during a ceremony at the SAA annual meeting in Portland, Ore., in July. The distinction of Fellow is the highest honor bestowed on individuals by the SAA and is awarded for outstanding contributions to the archives profession. Hackbart-Dean, who earned a master’s degree in history and archival management at UConn, was nominated for distinguishing herself as a thoughtful leader and a skilled teacher.

Pamela Hackbart-Dean ’87 MA, director of the Special Collections Research Center at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, was inducted as a Fellow of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) during a ceremony at the SAA annual meeting in Portland, Ore., in July. The distinction of Fellow is the highest honor bestowed on individuals by the SAA and is awarded for outstanding contributions to the archives profession. Hackbart-Dean, who earned a master’s degree in history and archival management at UConn, was nominated for distinguishing herself as a thoughtful leader and a skilled teacher.

![]() Marikate Murren ’89 (CLAS), ’96 MA was recently named vice president of human resources at MGM Springfield in Springfield, Mass., which is due to open in September 2017.

Marikate Murren ’89 (CLAS), ’96 MA was recently named vice president of human resources at MGM Springfield in Springfield, Mass., which is due to open in September 2017.

![]() Attorney Michael I. Flores ’89 (CLAS), of Orleans, Mass., was elected president of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, Massachusetts Chapter, for a two-year term starting in September. The national organization has about 1,200 of the most distinguished divorce and family law attorneys in the United States.

Attorney Michael I. Flores ’89 (CLAS), of Orleans, Mass., was elected president of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, Massachusetts Chapter, for a two-year term starting in September. The national organization has about 1,200 of the most distinguished divorce and family law attorneys in the United States.

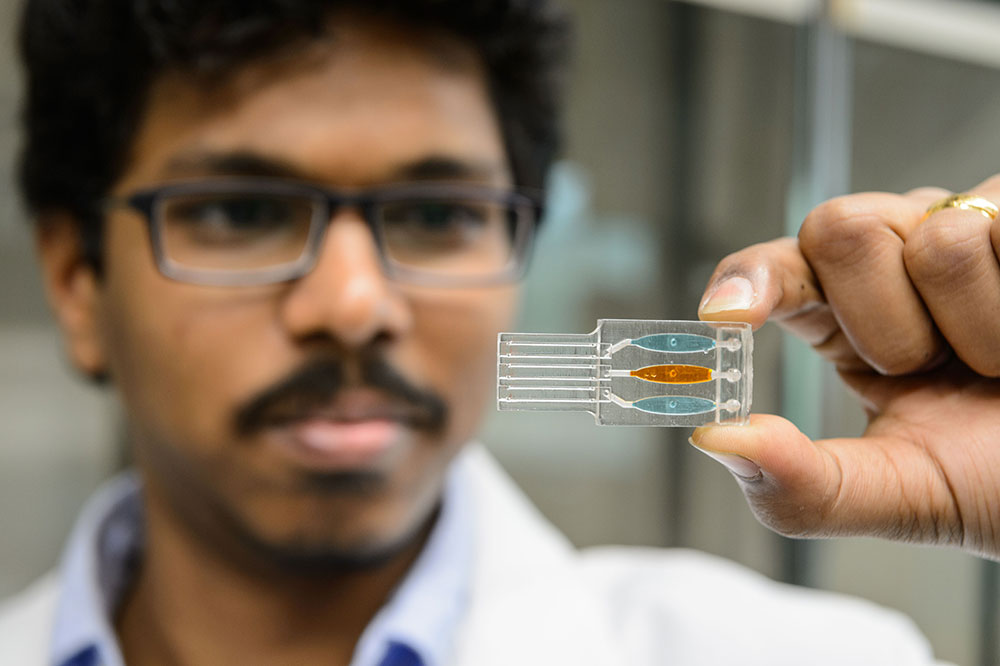

![]() Vladimir Coric, MD ’92 (CLAS) rang the opening bell of the New York Stock Exchange on May 9, 2017, after the company he founded, Biohaven Pharmaceutical Holding Company Ltd., went public. He reports that Biohaven raised $195 million in its IPO and was the largest biotech IPO at the time.

Vladimir Coric, MD ’92 (CLAS) rang the opening bell of the New York Stock Exchange on May 9, 2017, after the company he founded, Biohaven Pharmaceutical Holding Company Ltd., went public. He reports that Biohaven raised $195 million in its IPO and was the largest biotech IPO at the time.

![]() Jennifer Kaysen Rogers ’93 MA was promoted to associate director of employer relations at the University of St. Thomas Career Development Center in St. Paul, Minn.

Jennifer Kaysen Rogers ’93 MA was promoted to associate director of employer relations at the University of St. Thomas Career Development Center in St. Paul, Minn.

![]() Leighangela (Byer) Brady ’94 (Neag) ’95 MA was selected as superintendent of the National School District in San Diego, Calif., starting in the 2016”“’17 school year.

Leighangela (Byer) Brady ’94 (Neag) ’95 MA was selected as superintendent of the National School District in San Diego, Calif., starting in the 2016”“’17 school year.

![]() Rob Carolla ’94 (CLAS) was named president of the College Sports Information Directors of America (CoSIDA) for the 2017”“’18 academic year at the organization’s annual convention in Orlando. CoSIDA is a 3,000-plus-member association for college athletics communications professionals. Carolla had served as an officer there for the past three years.

Rob Carolla ’94 (CLAS) was named president of the College Sports Information Directors of America (CoSIDA) for the 2017”“’18 academic year at the organization’s annual convention in Orlando. CoSIDA is a 3,000-plus-member association for college athletics communications professionals. Carolla had served as an officer there for the past three years.

![]() William Rice ’94 (ENG) has been appointed assistant executive director for schools and curriculum at Area Cooperative Educational Services (ACES), a regional educational service center in New Haven, Conn. He oversees ACES schools and programs and works closely with ACES administrators and teachers to support innovative learning initiatives. Prior to ACES, Rice was the director of mathematics for Hartford Public Schools.

William Rice ’94 (ENG) has been appointed assistant executive director for schools and curriculum at Area Cooperative Educational Services (ACES), a regional educational service center in New Haven, Conn. He oversees ACES schools and programs and works closely with ACES administrators and teachers to support innovative learning initiatives. Prior to ACES, Rice was the director of mathematics for Hartford Public Schools.

![]() Jasmine Alcantara ’95 (CLAS), ’99 MBA, owner of JLA Group, was awarded the 2017 U.S. Women’s Chamber of Commerce Innovation & Performance Award at the National Small Business Federal Contracting Summit in Washington, D.C., on March 30, 2017.

Jasmine Alcantara ’95 (CLAS), ’99 MBA, owner of JLA Group, was awarded the 2017 U.S. Women’s Chamber of Commerce Innovation & Performance Award at the National Small Business Federal Contracting Summit in Washington, D.C., on March 30, 2017.

This prestigious award recognizes female small business owners who exhibit outstanding innovation and/or performance on a key contract that will significantly bolster their ability to secure future opportunities.

JLA Group provides a wide range of consulting and advisory services ”” such as strategic planning and communications, project management, change and performance measurement, acquisition strategy and execution, and proposal and grant development ”” to government clients and commercial industries.

![]() Stefanie (Pratola) Ferreri ’97 (PHARM) was recently promoted to clinical professor at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy in Chapel Hill, N.C. She is also the current president of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists and recently received the National Community Pharmacists Association Leadership Award. She lives in Durham, N.C., with her husband, Eric Ferreri ’95, and their 9-year-old twins.

Stefanie (Pratola) Ferreri ’97 (PHARM) was recently promoted to clinical professor at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy in Chapel Hill, N.C. She is also the current president of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists and recently received the National Community Pharmacists Association Leadership Award. She lives in Durham, N.C., with her husband, Eric Ferreri ’95, and their 9-year-old twins.

![]() John O’Hara ’97 MBA has joined ProHealth Physicians in Farmington, Conn., as a finance director. Previously, he had been director of Medicaid financial and business performance at Tufts Health Plan in Watertown, Mass.

John O’Hara ’97 MBA has joined ProHealth Physicians in Farmington, Conn., as a finance director. Previously, he had been director of Medicaid financial and business performance at Tufts Health Plan in Watertown, Mass.

![]() Lynn M. Patarini, BGS ’97, released her fifth novel, Uncle Neddy’s Funeral, in May under the pseudonym L.M. Pampuro.

Lynn M. Patarini, BGS ’97, released her fifth novel, Uncle Neddy’s Funeral, in May under the pseudonym L.M. Pampuro.

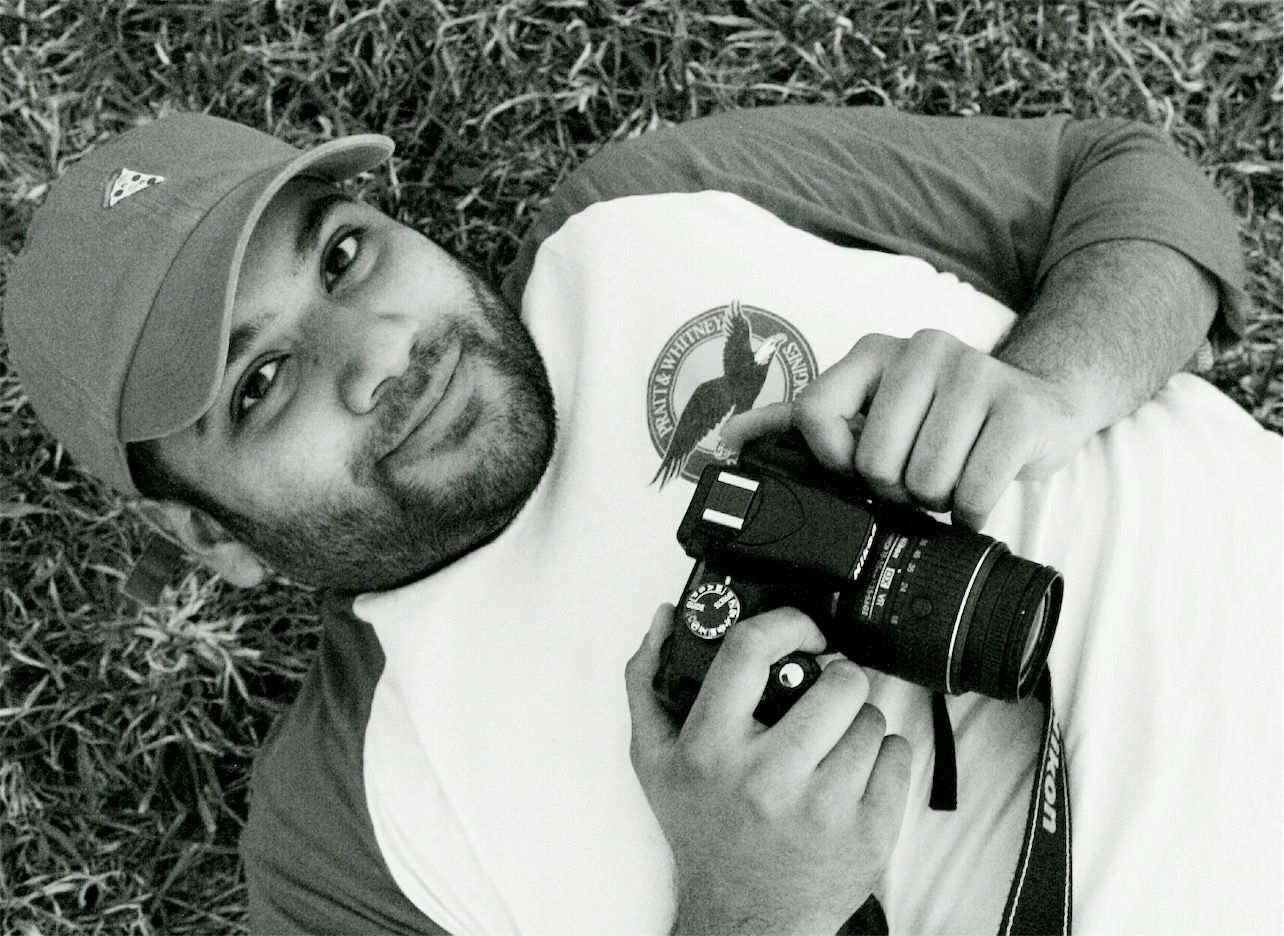

![]() Aimée Allaire ’98 (CLAS) reports that she recently passed the halfway mark of an intensive study on the importance of motherhood in the modern world. Her work has been indirectly sponsored by various Connecticut companies, including UTC Power and, currently, Bauer, Inc., in Bristol. She lives in Mystic with her husband, Keith Brainard ’98 (ENG), and their four children.

Aimée Allaire ’98 (CLAS) reports that she recently passed the halfway mark of an intensive study on the importance of motherhood in the modern world. Her work has been indirectly sponsored by various Connecticut companies, including UTC Power and, currently, Bauer, Inc., in Bristol. She lives in Mystic with her husband, Keith Brainard ’98 (ENG), and their four children.

![]() Steven R. Jenkins, CPA, ’99 JD, ’12 MBA, ’15 MA has been appointed as a trustee to the Connecticut Laborers’ Pension, Health, and Annuity Funds. He is general counsel and compliance director for regional construction firm Manafort Brothers Inc., headquartered in Plainville, Conn.

Steven R. Jenkins, CPA, ’99 JD, ’12 MBA, ’15 MA has been appointed as a trustee to the Connecticut Laborers’ Pension, Health, and Annuity Funds. He is general counsel and compliance director for regional construction firm Manafort Brothers Inc., headquartered in Plainville, Conn.

![]() Michael Boecherer ’00 (CLAS), ’02 MA and his wife, Victoria, welcomed Nora Johnston Boecherer in June 2017. Baby Nora weighed in at 6 lbs., 6 oz. and measured 17 ½ inches long. Mom and baby are both healthy, and Papa is happy to be outnumbered two to one.

Michael Boecherer ’00 (CLAS), ’02 MA and his wife, Victoria, welcomed Nora Johnston Boecherer in June 2017. Baby Nora weighed in at 6 lbs., 6 oz. and measured 17 ½ inches long. Mom and baby are both healthy, and Papa is happy to be outnumbered two to one.

![]() Kate Moran Connolly ’03 (CAHNR) is a physician’s assistant in the Burn Unit at Bridgeport Hospital. After graduating from UConn, she worked as a registered dietician at Bridgeport Hospital for several years. She earned her master’s in physician assistant studies at Philadelphia University in 2010, recently became a mother, and just spent a year as Bridgeport Hospital’s Employee of the Year.

Kate Moran Connolly ’03 (CAHNR) is a physician’s assistant in the Burn Unit at Bridgeport Hospital. After graduating from UConn, she worked as a registered dietician at Bridgeport Hospital for several years. She earned her master’s in physician assistant studies at Philadelphia University in 2010, recently became a mother, and just spent a year as Bridgeport Hospital’s Employee of the Year.

![]() Niamh (Cunningham) Emerson ’06 (CLAS) recently joined the Yale School of Nursing advancement team as associate director of development and alumnae affairs. She was most recently employed in Yale University’s Office of the Secretary as assistant secretary for corporation affairs, where she was responsible for the logistics of all aspects of Yale Corporation (board of trustees) and University Council meetings and was the staff liaison for the Corporation Honorary Degrees Committee.

Niamh (Cunningham) Emerson ’06 (CLAS) recently joined the Yale School of Nursing advancement team as associate director of development and alumnae affairs. She was most recently employed in Yale University’s Office of the Secretary as assistant secretary for corporation affairs, where she was responsible for the logistics of all aspects of Yale Corporation (board of trustees) and University Council meetings and was the staff liaison for the Corporation Honorary Degrees Committee.

![]() Dr. Ryan Denley ’06 (CAHNR) graduated from the School of Allied Health with a BS in diagnostic genetic sciences in 2006. He worked as a cytogenetic technologist for five years after graduation, then graduated from the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in 2015. He married Dr. AnnaMaria Arias in May 2016 and, most recently, was selected chief resident of internal medicine at Morristown Medical Center in N.J. Upon completion of his residency, he intends to pursue a fellowship in hematology/oncology.

Dr. Ryan Denley ’06 (CAHNR) graduated from the School of Allied Health with a BS in diagnostic genetic sciences in 2006. He worked as a cytogenetic technologist for five years after graduation, then graduated from the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in 2015. He married Dr. AnnaMaria Arias in May 2016 and, most recently, was selected chief resident of internal medicine at Morristown Medical Center in N.J. Upon completion of his residency, he intends to pursue a fellowship in hematology/oncology.

![]() Jesse M. Krist ’08 (CLAS) and Kimberley A. Sadowski ’09 (BUS) celebrated their one-year wedding anniversary in April. They were married in Siena, Italy, in April 2016.

Jesse M. Krist ’08 (CLAS) and Kimberley A. Sadowski ’09 (BUS) celebrated their one-year wedding anniversary in April. They were married in Siena, Italy, in April 2016.

![]() Alphie Aiken ’08 MBA was honored at the Women in Business Summit on April 21, 2017. She is president of Junior Achievement Jamaica and previously spent 15 years at General Electric Co. Most recently, she was an eBusiness leader, overseeing $600 million in online sales annually. She has led the GE Women’s Network for Greater Hartford, as well as the GE African American Forum in the Northeast.

Alphie Aiken ’08 MBA was honored at the Women in Business Summit on April 21, 2017. She is president of Junior Achievement Jamaica and previously spent 15 years at General Electric Co. Most recently, she was an eBusiness leader, overseeing $600 million in online sales annually. She has led the GE Women’s Network for Greater Hartford, as well as the GE African American Forum in the Northeast.

![]() Kerry (Coffey) Welton ’10 (CLAS) and Jeffrey Welton ’08 (BUS) are proud to announce the birth of their daughter, Madeline Dina, in March 2017. “Born a Husky fan!” say her parents.

Kerry (Coffey) Welton ’10 (CLAS) and Jeffrey Welton ’08 (BUS) are proud to announce the birth of their daughter, Madeline Dina, in March 2017. “Born a Husky fan!” say her parents.

![]() Brien Buckman ’12 (CLAS) and Alicia (Kruzansky) Buckman ’12 (CLAS) were married Nov. 20, 2016, in West Hartford, Conn. They now live in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Brien Buckman ’12 (CLAS) and Alicia (Kruzansky) Buckman ’12 (CLAS) were married Nov. 20, 2016, in West Hartford, Conn. They now live in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

![]() Nicole Lavoie ’12 (ENG) and Jordan Smith ’12 (ENG) were married June 4, 2017, in Bolton, Conn. surrounded by a large group of UConn friends.

Nicole Lavoie ’12 (ENG) and Jordan Smith ’12 (ENG) were married June 4, 2017, in Bolton, Conn. surrounded by a large group of UConn friends.

In Memoriam

Below is a list of deaths reported to us since the last issue of UConn Magazine.

Please share news of alumni deaths and obituaries with UConn Magazine by sending an email to: alumni-news@uconnalumni.com or writing to Alumni News & Notes, UConn Foundation, 2384 Alumni Drive Unit 3053, Storrs, CT 06269.

Alumni

![]() Robert David Mariconda ’73 (CLAS)

Robert David Mariconda ’73 (CLAS)

May 4, 2007

![]() Reena “Connie” Trunk Fink ’54 (CLAS)

Reena “Connie” Trunk Fink ’54 (CLAS)

Oct. 22, 2016

![]() John Petrucelli ’77 (ENG)

John Petrucelli ’77 (ENG)

Jan. 21, 2017

![]() Kathryn Shapiro Rubin ’79 MSW

Kathryn Shapiro Rubin ’79 MSW

Jan 29, 2017

![]() Anthony C. Chapell ’48 (CLAS), ’49 MS

Anthony C. Chapell ’48 (CLAS), ’49 MS

Feb. 5, 2017

![]() Edward Allen Rothman ’55 (ENG)

Edward Allen Rothman ’55 (ENG)

Feb. 9, 2017

![]() Herbert Raymond Tschummi ’50 (BUS)

Herbert Raymond Tschummi ’50 (BUS)

Feb. 23, 2017

![]() Steven F. Conti ’82 (CLAS)

Steven F. Conti ’82 (CLAS)

Feb. 24, 2017

![]() Sister Patricia Coughlin ’50 (CLAS)

Sister Patricia Coughlin ’50 (CLAS)

March 1, 2017

![]() Deborah Chase ’87 MA

Deborah Chase ’87 MA

March 5, 2017

![]() Gloria Bidwell ’51 (CLAS)

Gloria Bidwell ’51 (CLAS)

March 5, 2017

![]() John D. Adams ’59 JD

John D. Adams ’59 JD

March 8, 2017

![]() Thomas C. Burrill ’66 (RHSA)

Thomas C. Burrill ’66 (RHSA)

March 25, 2017

![]() Barbara Goossen Capelle ’50 (CLAS)

Barbara Goossen Capelle ’50 (CLAS)

April 6, 2017

![]() Francoise O. Alshuk ’57 (BUS), ’97 MSW

Francoise O. Alshuk ’57 (BUS), ’97 MSW

April 7, 2017

![]() Julio Loureiro ’63 MS

Julio Loureiro ’63 MS

April 7, 2017

![]() Robert Hall ’54 (CLAS)

Robert Hall ’54 (CLAS)

April 8, 2017

![]() Dorothy (Kalinauskas) Bowen ’53 (CLAS)

Dorothy (Kalinauskas) Bowen ’53 (CLAS)

April 9, 2017

![]() Judith Larson ’70 (NEAG)

Judith Larson ’70 (NEAG)

April 9, 2017

![]() Frederick J. Prior ’62 (BUS)

Frederick J. Prior ’62 (BUS)

April 12, 2017

![]() Howard E. Katz ’59 (BUS)

Howard E. Katz ’59 (BUS)

April 14, 2017

![]() Ronald K. Jacobs ’52 JD

Ronald K. Jacobs ’52 JD

April 14, 2017

![]() John T. Bell ’54 (CLAS)

John T. Bell ’54 (CLAS)

April 15, 2017

![]() Ira “Bob” Wasniewski ’52 (CAHNR), ’55 MA

Ira “Bob” Wasniewski ’52 (CAHNR), ’55 MA

April 19, 2017

![]() Jerome S. Nisselbaum ’49 (CLAS)

Jerome S. Nisselbaum ’49 (CLAS)

April 20, 2017

![]() John Tumicki ’52 (BUS)

John Tumicki ’52 (BUS)

April 20, 2017

![]() Irwin Hausman ’65 (CLAS), ’68 JD

Irwin Hausman ’65 (CLAS), ’68 JD

April 22, 2017

![]() Joseph J. Vitali ’54 (CLAS)

Joseph J. Vitali ’54 (CLAS)

April 22, 2017

![]() Robert Samuel Hussey ’52 (BUS)

Robert Samuel Hussey ’52 (BUS)

April 22, 2017

![]() Donald Francis Fenton ’57 (CLAS) ’13 JD

Donald Francis Fenton ’57 (CLAS) ’13 JD

April 25, 2017

![]() Troy Antwon Walcott Sr. ’02 (CLAS)

Troy Antwon Walcott Sr. ’02 (CLAS)

April 27, 2017

![]() Rachel Parsons ’07 (CLAS)

Rachel Parsons ’07 (CLAS)

April 28, 2017

![]() James B. Carroll ’67 Ph.D

James B. Carroll ’67 Ph.D

April 29, 2017

![]() Rita Gerzanick ’56 MA

Rita Gerzanick ’56 MA

April 29, 2017

![]() Charles M. Hensgen, MD, ’70 MS

Charles M. Hensgen, MD, ’70 MS

April 30, 2017

![]() Toby Kimball ’65 (BUS)

Toby Kimball ’65 (BUS)

May 1, 2017

![]() Carolyn W. Arnold ’86 (CCS)

Carolyn W. Arnold ’86 (CCS)

May 3, 2017

![]() Martha D. “Pepper” Hitchcock

Martha D. “Pepper” Hitchcock

May 3, 2017

![]() Ambrose M. Fiorito ’57 (BUS)

Ambrose M. Fiorito ’57 (BUS)

May 5, 2017

![]() K. Scott Christianson ’69 (CLAS)

K. Scott Christianson ’69 (CLAS)

May 14, 2017

![]() Francis Mike Dunn ’62 (BUS)

Francis Mike Dunn ’62 (BUS)

May 18, 2017

![]() Patricia H. Ferguson year ’77 MA

Patricia H. Ferguson year ’77 MA

August 17, 2017

Faculty & Staff

![]() Â Alexinia Young Baldwin, ’72 Ph.D

Alexinia Young Baldwin, ’72 Ph.D

Jan. 21, 2017

Alexinia Young Baldwin, ’72 PhD, emeritus professor of education, died Jan. 21, 2017. After graduating from Tuskegee University and earning a master’s at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a music and physical education teacher in the Birmingham, Ala. Public Schools, where she became a teacher of the first gifted class for black students in the city. She then earned her doctorate at the University of Connecticut and became a professor of curriculum and education for the gifted at the University of New York at Albany. She returned to UConn as a full professor and chair of the department of curriculum and instruction. She was a civil rights litigant in the landmark case of Baldwin vs. the City of Birmingham over the desegregation of the Terminal Station waiting room. This litigation established a non-segregation rule for the entire country. She was also the first minority president of Altrusa International, Inc., Service Organization for Executive and Professional women in 1999.

![]() Â Tom Lewis

Tom Lewis

Jan. 26, 2017

Tom Lewis, an associate professor-in-residence in the UConn Geography Department, died Jan. 26, 2017. He spent 15 years at UConn, after teaching 29 years at Manchester Community College. He also served as the Connecticut Geographic Alliance Coordinator for many years. He had a tremendous impact on geography and geography education in Connecticut and much further afield.

![]() Â Michael Gerald

Michael Gerald

Feb. 4, 2017

Michael Gerald, former dean of the UConn School of Pharmacy who was known for his instrumental leadership and love of teaching, died Feb. 4, 2017. He graduated from Fordham University’s College of Pharmacy and received a commission from the U.S. Air Force as a second lieutenant. He began his career at The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy in 1969 as an assistant professor of pharmacology. He moved up the ranks, eventually becoming associate dean.

At UConn, Dr. Gerald helped the School of Pharmacy move from a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy to a Doctor of Pharmacy program and greatly expanded the clinical faculty. He also played a major role in developing the new Pharmacy-Biology Building. As much as Dr. Gerald enjoyed his role as dean, he also loved his time spent teaching where he was able to work closely with students.

![]() Sigmund “John” Montgomery

Sigmund “John” Montgomery

Feb. 27, 2017

Accounting Professor Sigmund “John” Montgomery, who helped develop the graduate business programs portfolio at UConn, including the MBA program in Stamford, died Feb. 27, 2017. He was known as a demanding professor with high standards and expectations. He was among a core group of dedicated faculty who anchored the undergraduate and graduate programs at Stamford and established high principles for the adjunct faculty as well.

After graduating from Columbia University, he served in the 8th Air Force, becoming a Major with a Bronze Star. He returned to Columbia, becoming an assistant professor at Columbia’s Engineering School. He earned a doctorate in accounting from NYU’s Stern School of Business and then moved to UConn where he taught at the Stamford campus.

![]() Â Ralph Porter Collins

Ralph Porter Collins

March 9, 2017

Ralph Porter Collins, emeritus professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, died March 9, 2017. He grew up in Alpena, Mich. and earned a BS, MS, and a Ph.D. in botany and plant pathology from Michigan State University. In 1957, he began his career at the University of Connecticut as an instructor in botany. He retired from UConn in 1989 as a full professor and head of the botany section. After leaving UConn, Collins took a research position with the National Cancer Institute as an AIDS Expert in the Division of Cancer Treatment, retiring in 2001.

![]() Â Joseph J. Comprone

Joseph J. Comprone

May 1, 2017

Dr. Joseph J. Comprone, UConn professor emeritus of English, who was an inspirational leader and a pioneer in rhetoric and composition, died in Louisville, Ky., on May 1, 2017. He served as associate vice provost at the Avery Point campus from 2002 to 2010, and taught English at Avery Point and then at Hartford until 2014.

His goal was to build programs and campuses that would best nurture and serve the needs of students, faculty, and community alike. One of his proudest achievements was the student center on the Avery Point campus. Among his accomplishments, he wrote five books, published more than 50 articles, and directed 20 dissertations, helping to shape generations of scholarship in rhetoric and composition.

Share your news with UConn Nation!

Your classmates want to know about the milestones in your life. Send news about weddings, births, new jobs, new publications, and more to:Â alumni-news@uconnalumni.com

Submissions may be edited for clarity or length.