UConn:

The Heart

of Hartford

Restoring the grand Hartford Times building is just the beginning of what having UConn back in downtown Hartford will mean for the city. The energy these students bring will be “a complete game changer.”

By Rand Richards Cooper | Photos by Peter Morenus

The past half-century has not been kind to Connecticut’s capital. Against a fading memory of Hartford in its heyday — a cultural and commercial center that drew visitors from all over New England — the city languished. Thriving cities exert a gravitational force on communities around them, pulling people in. But in Hartford the force dwindled. City planners razed old neighborhoods, laid down highways to facilitate suburban access, and built gleaming office palaces. Over time the city center became a place that emptied out at 5 p.m. Fewer people came in at night and on weekends. Downtown effectively died.

This is a test of the beaver builder update. Anyone hoping to revitalize a city’s downtown faces a stubborn paradox. To get people there, you need amenities. To justify and attract amenities, you need people. How to break into that cycle and restore a city’s gravitational force?

In August a key piece of the puzzle clicked into place, with the opening of the University of Connecticut’s Hartford campus. UConn’s former West Hartford branch now occupies a stretch of Prospect Street, parallel to Main Street, reaching from the Hartford Public Library north to Constitution Plaza and the UConn School of Business. The move installs some 3,400 students, faculty and staff in the heart of downtown’s Front Street district, alongside the Wadsworth Atheneum, City Hall, the Public Library, the Travelers, and the Hartford Club.

For University President Susan Herbst, the decision to relocate was a no-brainer. “When I came to UConn and heard that the Greater Hartford campus was actually in West Hartford, I was surprised and, frankly, disappointed.” With the campus experiencing dilapidation and facing a multimillion-dollar overhaul, the time was right for a move. Herbst knew exactly where UConn needed to go.

“We really wanted to bolster our connection to the city and be part of the resurgence of Hartford,” says Herbst. She points out that before opening the suburban campus in 1970, UConn had been in Hartford, occupying several different locations, going back nearly a century. “So this is really a homecoming for us.”

The project was a big push, Herbst admits. “Let’s face it, people don’t like to move. But I have been stunned by the gush of positivity and enthusiasm for doing this.”

Main UConn building

Hartford Public Library

Wadsworth Atheneum

Travelers Tower

Constitution Plaza

Connecticut Science Center

Front Street

Connecticut Convention Center

A College Town

“The UConn campus is a game changer for the city,” says Matt Ritter, a Hartford state representative and the House Majority leader. “Adding thousands of young people downtown will bring an energy we haven’t seen in some time.” Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin says the move is crucial to the city’s “long-awaited revitalization; the new students will be a big part of making Hartford a more lively, vibrant place.”

To get why Hartford is so excited, you have to understand the special, galvanizing role colleges and universities play in boosting a city’s dynamism. Students are often the first wave of an urban renaissance. Visit any number of thriving medium-sized cities across the country, from Providence to Asheville to Boulder, and you instantly see and feel the vitality supplied by students and recent graduates. Where they pop up, restaurants, galleries, and entertainment venues soon follow.

And eventually companies do, too. “Bringing UConn into Hartford is an obvious and necessary thing to do,” says Bruce Becker, an architect and developer who converted the former Bank of America building into apartments at 777 Main, a short walk from the new campus. Becker is currently in discussion to relocate a suburban company to retail space in his building. “The only reason they’re thinking about it is the growing reputation of Hartford as an attractive place to work,” he says.

For years, Hartford residents have glanced peevishly at Providence or New Haven and said, “Well, if you took a world-class university and put it down in the middle of our city, we’d look pretty good too!” And while that hasn’t happened in one fell swoop, Hartford has been assembling a higher-education corridor at its center, one piece at a time. Trinity College is moving a graduate program to Constitution Plaza, partnering with Capital Community College, located in the refurbished G. Fox building just up Main Street. The University of St. Joseph has its pharmacy school nearby. There’s Rensselaer Polytechnic’s Hartford campus. And now, capping it off in a big way, is UConn.

UConn students, a large majority of them from Connecticut, represent the next generation of homegrown professionals — exactly the people a city like Hartford needs to attract. In this sense, the downtown campus represents an urban field of dreams: If you build it, they will come. And if they like it, they will stay.

“We want that 7-year-old to be able to go up, hands pressed against the glass, and see what that student is doing.”

UConn Hartford PUBLIC Library Director michael howser

“We want that 7-year-old to be able to go up, hands pressed against the glass, and see what that student is doing.”

UConn Hartford PUBLIC Library Director michael howser

MAKING CITIZENS

The centerpiece of that field of dreams is the remarkable new building UConn has created from the former Hartford Times offices. The Times was a daily paper that operated, in fierce competition with the Courant, from 1817 to 1976. Built in 1920, the Beaux-Arts building that housed it for the last half-century of its run was itself already a novel reclamation project. Its architect, Donn Barber, who also designed the iconic Travelers Tower across the street, salvaged granite columns, massive oak doors, and marble steps from the Madison Square Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. He redeployed these elements in the Times’ monumental portico, conferring a sense of the sacred. The high walls of the portico’s arcade are decorated with murals depicting allegorical figures for Poetry and Prose, Time and Space, Insight and Inspiration.

Preservationists have long viewed the Hartford Times building as a treasure, and shuddered at the thought of its demolition. Its importance is more than mere architectural beauty. Buildings like this are a city’s “good bones.” They carry the city’s stories in them, forming enduring points of civic reference. Four U.S. presidents spoke from the terrace of the Times building — including John F. Kennedy, who gave the final speech of his 1960 campaign, one day before he was elected. “We preserve historic buildings because they give us a sense of our past and tie that past to us,” says Sara Bronin, an architect and UConn Law professor who chairs Hartford’s Planning and Zoning Commission (and is the wife of Mayor Luke Bronin.)

From the start, Susan Herbst was committed to saving the Times building, viewing it as a way for UConn to honor the state’s history while situating the university’s new campus in the cultural, governmental, and business nerve center of the city. Herbst also perceived an institutional continuity with a newspaper whose offices lauded “Insight” and “Inspiration.”

“The building is very high-minded,” she says with obvious enthusiasm. “It really fits with our own public mission as a university dedicated to making citizens.”

Preserving it was not simple. The renovation involved shearing off the old structure’s facade and wings, then joining them to a roughly 140,000-square-foot new building. To do the job, UConn hired RAMSA, the renowned New Haven and Manhattan based firm headed by Robert A.M. Stern, former Dean of the Yale School of Architecture, whose resumé includes Yale’s recent $500 million expansion. “Stern is a really talented designer,” says Sara Bronin. “He’s known for neo-traditional institutional buildings, and that’s why he was the right choice for this project. It’s a super flashy project for our city.”

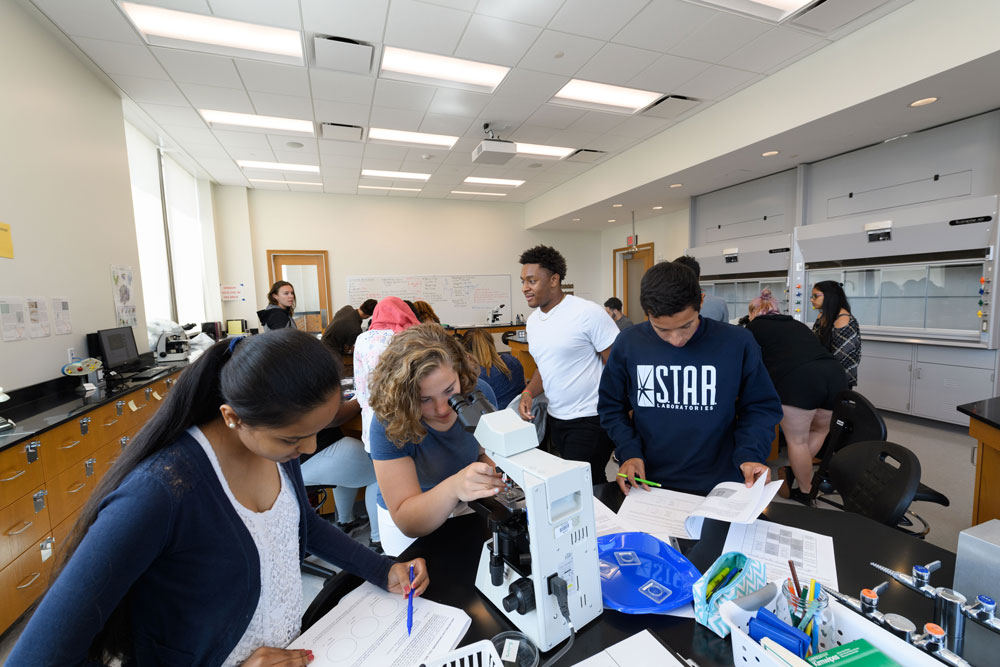

The building, with its bold neoclassicism, offers plenty of wow factor. Students entering from Prospect Street ascend one of two winding staircases and pass through giant arched doors to an interior that matches the facade for grandeur. At the center is a three-story high atrium, naturally lit via a steel-and-glass facade to the south, with massive square limestone columns girding the space and adding to its imposing beauty and strength. Mezzanines look down over a student collaboration area, on an elevated platform beneath circular halo lights, to the terrazzo floor below, where students will hang out. “It’s equipped in state-of-the-art ways that reflect how people learn,” says Herbst, adding with a laugh, “let’s just say that there are a lot of outlets!”

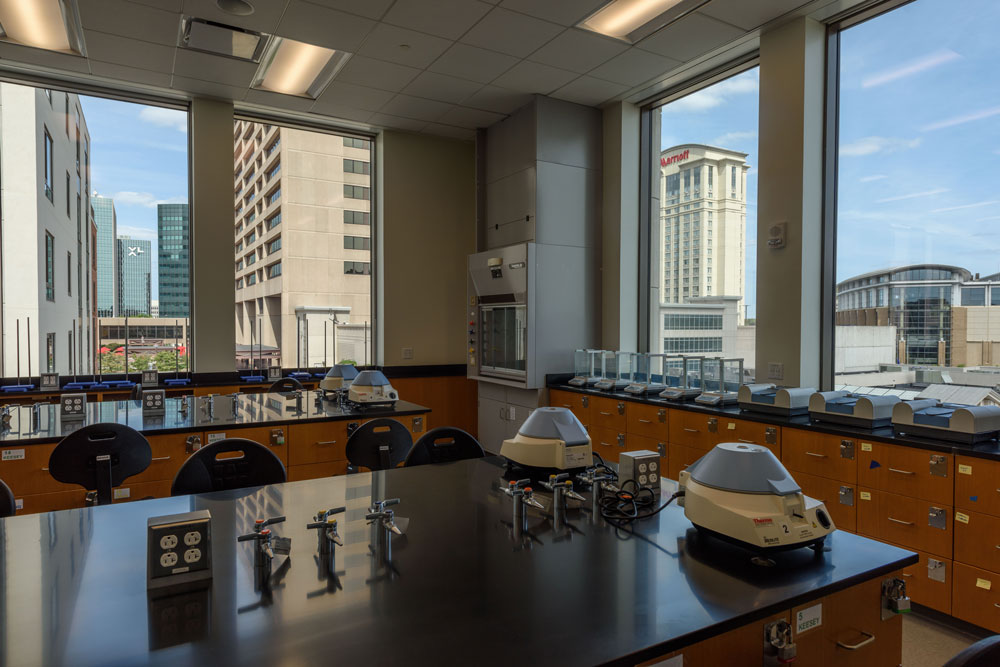

The five-story building houses classrooms and labs, meeting and work areas, and faculty and administration offices. The atrium opens to a south-facing courtyard, landscaped with trees and grass. Oversized windows in the science labs offer views so enticing, one worries about experiments gone awry. Faculty offices on the top floors boast panoramic vistas of city and countryside. A wood-paneled conference room overlooks the atrium through floor-to-ceiling windows. It’s a soaring building, bright with natural light. Says James Libby, UConn’s Design Project Manager for the campus: “We’re setting a new standard for how these buildings look.” Architect Bruce Becker agrees. “This is a flagship type of building,” he says. “It brings a whole new educational institution not of the scale of Yale, but of the quality.”

“The city has a lot to offer ... This building represents a big investment for UConn and for the state. It’s worth it. And it’s forever.”

UCONN President Susan Herbst

UConn President Susan Herbst and UConn Hartford Director Mark Overmyer-Velázquez in a fifth floor meeting space. The orange through the window is the iconic Alexander Calder “Stegosaurus” statue.

Taking it to the streets

When you tour the new building, with all its gleaming amenities, you’ll notice something that is not there: a place to eat. This omission-by-design is intended to send hungry students out into the neighborhood, and reflects lessons learned in other, similar relocations.

“We don’t want our building to be a vault,” says Herbst. “I decided early on, no food service in the building. We must have students out on the street!”

Students out on the street: the phrase surely has a different valence than it would have had fifty years ago, and its significance is not lost on Jamie “The Bear” McDonald, the barbecue impresario whose five Hartford-area restaurants include two in the Front Street business zone adjacent to the new UConn campus. McDonald says that the new building’s lack of food and function spaces will benefit hotels and restaurants in the vicinity. “We can do the catering for small-group functions, faculty meetings, and the like. That’s the key thing about the new campus — it’s not an island. It’s integrated with the community, and we’ll get the benefit.”

The new campus has been planned and designed to maximize connection to the neighborhood in a host of ways. Students use the same parking garages everyone else does. Ground-floor retail spaces in the main building open both to the street and to the atrium. At the campus’s southwest corner, a grand plaza welcomes the Hartford community and links diagonally to the landscaped courtyard, also publicly accessible. The Barnes & Noble UConn, the first bookstore in downtown Hartford in many years, occupies the ground floor of the Front Street Lofts across the street. A new CVS is in 777 Main, a few blocks away. Lectures and perhaps classes will be held in the Atheneum across the street. Large-scale events can use the Infinity Hall concert venue or the Science and Convention Centers just down the street. And discussions are underway for a plan whereby students can use Husky Bucks at neighborhood businesses.

The emphasis on community is especially fitting for the School of Social Work, which moved into a stately brick building at 38 Prospect Street early this summer. “Being in downtown Hartford will make it really easy to connect with organizations,” notes Lauren Chapman, a 23-year-old graduate case-work student from Hebron. Chapman believes that the campus’s setting makes it more than a mere commuter school. “People will stick around and use the area, both between classes and after. You couldn’t do that at West Hartford. Here people can go into a restaurant or cafe or bar and socialize, or get some work done. It’s conducive to that.”

These sentiments are echoed by Chapman’s teacher, social work professor Lisa Werkmeister-Rozas. “It was always strange for us to be in a suburban setting,” she observes. “Our students are dealing with urban populations, and now they can see the everyday situations that their clients talk about. I think it will be a really important learning experience.” The move is practical, Werkmeister-Rozas says, since many social-work internships are based in the city. “And from a pure advocacy perspective, being able to participate in the renewal of Hartford is a good thing.”

No feature of the new campus better illustrates the town-gown symbiosis than the arrangement with Hartford Public Library, where a $4 million renovation will facilitate use by as many as 1,000 students a day, with classes taking place in several new classrooms. UConn students will enter via the Arch Street entrance, passing a massive 1870 Colt’s Universal Platen Press. Inside, they’ll find an impressive array of more contemporary information technologies, like a video studio where professors can record lectures using a virtual blackboard, or the Digital Scholarship Studio, where up to 12 screens can be mosaiced together so that research teams can compare data dashboards.

Library staff on both sides are thrilled about the joint effort. “We’ve been focused on collaboration from day one,” says UConn Hartford Public Library Director Michael Howser. Brenda Miller, who heads the Hartford History Center at HPL, lists the contributions UConn has already made, from a baby grand piano for the library’s popular jazz series, to support for a Learning Lab, to a new storage unit to house the library’s historical collection. The partnership will enable a broad array of events and programming, like a recent series of discussions on the founding documents of American democracy, developed with UConn’s Public Humanities Institute and the Wadsworth Atheneum. Already the library has hosted a drop-in writing workshop conducted by a UConn professor, where city residents could bring in a poem, resume, or application letter and get help with it.

The new spaces in the library have been configured to spur interaction between UConn students and the general public. “There’s no bouncer at the door, no gatekeeper,” says Howser. “We want to be open and welcoming.” Anyone with a Hartford Library card can borrow from UConn’s books. The new layout offers joint study areas and classrooms; there’s a conference room with glass walls on both sides, making it totally transparent. “We want people to see the students in action,” says Howser. “We want that 7-year-old to be able to go up, hands pressed against the glass, and see what that student is doing.” In addition to the many tangible benefits, the UConn presence will offer a standing role model for urban kids from non-college-educated backgrounds.

“Hartford Public Library is a cornerstone of democracy, open to anyone,” observes the library’s Director of Communications, Don Wilson. “But the one segment we haven’t had en masse is college students. There’s an ecosystem here, and when students are introduced into that, both sides will benefit. I’m very excited to see what happens.”

Going Up

And so are Hartford residents — excited not merely about the library, but about the overall impact of UConn. Those of us who have lived here over the last 20 years can recite a litany of losses and failures, indignities and dashed hopes. The demoralizing departure of the city’s only major-league sports franchise, the NHL Whalers, and the subsequent sorry attempt to lure the Patriots. The ouster of a mayor charged with corruption. The city’s designation, at one point, as the second poorest in the U.S., after Brownsville, Texas.

Amid such slings and arrows, hope has always persisted, and we have eagerly reached for Mark Twain’s celebrated line about reports of one’s death being greatly exaggerated. Now, at last, the quip seems apt. Hartford faces significant ongoing challenges, but signs of a downtown resurgence abound, reflected in rising rents and real-estate values, new residences with high occupancy rates, flourishing restaurants, and the success of citizen initiatives such as Riverfront Recapture. Months ago the historic Goodwin Hotel re-opened after nearly a decade. Come next year, true commuter rail will connect the city efficiently to New Haven, and by extension New York. Meanwhile, painters and sculptors, designers, photographers, and other arts and entertainment entrepreneurs are incubating small-business ideas and energies. From Coltsville to Dunkin’ Donuts Park, a rejuvenation is underway. UConn’s new campus puts a gleaming seal on the deal.

“Lively, diverse, intense cities,” wrote Jane Jacobs in her influential 1961 book, The Death and Life of American Cities, “contain the seeds of their own regeneration.” Jacobs insisted that restoring a city’s gravitational pull means building on what is already there — developing precious resources, rather than trying to obliterate them and start anew. That effort is the essence of the new Hartford campus. It represents the state’s commitment to deploy the knowledge economy in boosting its capital city’s vitality while building on its tradition.

The benefit promises to be mutual. For UConn students, Hartford provides another option, one that will excite those eager for an urban experience and all it involves. “The city has a lot to offer,” says President Herbst. “We needed a stronghold there.” Anchoring that stronghold is a building she calls a metaphor for excellence.

“This building represents a big investment for UConn and for the state,” she says. “It’s worth it. And it’s forever.”

“the new students will be a big part of making Hartford a more lively, vibrant place.”

hartford Mayor luke bronin

Rand Richards Cooper’s writing has appeared in Harper’s, Esquire, The Atlantic, and The New York Times. Cooper, who is a contributing editor at Commonweal, lives with his wife and daughter in Hartford and writes a monthly column, “In Our Midst,” for Hartford Magazine.

Test Comment

Test Reply

Test Comment 2.