Flocking to Storrs

A BIRDER’S TOUR of CAMPUS

Ornithology professor Margaret Rubega told us “birds are everywhere.” Then she proved it. By Lisa Stiepock

Hardcore birders like to get out into the world early, which is how this magazine’s art director and I found ourselves meeting associate professor Margaret Rubega for the first of a series of campus bird walks at precisely 6 a.m. at a Storrs Center café.

All three of us clutching extra-large coffees, we stepped into the parking lot at 6:06 just as a magnificent red-tailed hawk swooped over street and sidewalk some 10 yards across the parking lot and at eye level ”” as if on cue.

“That’s amazing,” I said. To which Rubega replied, “No it’s not. Birds are everywhere.”

If there’s one message this 20-year UConn professor is trying to impart to her students and, as Connecticut State Ornithologist, to the community at large, it’s this one: Stop to look, and not incidentally to listen, and you will find birds, literally, everywhere.

A breakthrough teaching moment came for Rubega when she decided to take the technology that was keeping students from observing the world around them, aka their cellphones, and turn it into a weapon for her side, the side of good, of nature, of looking out and up.

She decided to give her students a graded assignment to find birds in their day-to-day lives and to tweet about what they see. “At first they think the assignment is boring and I’m a crazy lady,” says Rubega. But about four weeks into the semester she gives them a pop quiz asking whether having this assignment has changed anything in their day-to-day lives.

“Overwhelmingly the response comes back, ”˜Now I see birds everywhere!’” she says, with a smidgen of smugness. “They’ll post how they never noticed how little a gull flaps while in the air or that the feeding behavior of turkey vultures is fascinating. They turn into observers and that’s the whole point.”

Rubega chose Twitter not because of its bird-friendly branding, but because it appeals to this age range and the 140-character limit forces students to really think about how they are describing birds, to focus on the characteristics that are key.

“People deride Twitter for being 140 characters as if the content itself must be trivial because it’s brief,” says Rubega. Every good writer knows it’s much harder to pack meaning into short statements. And there’s no question that it is possible to be trivial at great length.”

What counts, she says, is what you do with the medium at hand. “And what I see students doing with Twitter is experimenting and then reporting to the rest of the world. What more can we ask from students whom we hope will turn into scientists?”

Enough Twitter talk, it’s time now for the three of us to get moving. Six a.m., it turns out, is for amateurs. “All the birds start singing before sunrise,” says Rubega, who is about to show us her favorite birding spots. Though birds are indeed everywhere, there are places where the number and variety of birds is bigger and better, which is why we are headed first to what Rubega calls “the big Kahuna” of Storrs campus birdwatching: Horsebarn Hill.

Twitter posts like the following are indicative of the tweets Rubega and her students post about birds they discover on campus and elsewhere. Other schools have gotten in on the act andyou can, too ”” at #birdclass.

Bird Photos by Mark Szantyr

Landscape Photos by Peter Morenus

Bird Photos by Mark Szantyr

Landscape Photos by Peter Morenus

People think of Horsebarn Hill as a great sunset spot. But this area near the actual horse barns is gorgeous at dawn, when you’ll see and hear a symphony of birds, including red-winged blackbirds, larks, thrushes, swallows, sparrows, hawks, wrens, finches, and more ”“ all bathed in the pinks and oranges of early morning.

Horsebarn Hill

Punctuated by the snorts and whinnies of horses anticipating breakfast we hear a cacophony of shrill red-winged blackbird whistles and shrieks. The birds are, says Rubega, “on territory” in the grasses of a small wetland at the base of the meadow that is the largest UConn horse field.

“Look at me, check me out,” chirps Rubega channeling a male with particularly brilliant red and yellow epaulets who has just flown past and perched on a nearby fence, unseating another male redwing. “Check me out,” she says continuing to channel the bird. “Sooo sexy, look at my epaulets. Hear my cry: I’m a man and this corner is my territory.”

Rubega points out a female redwing, which is shorter, squatter, and all spackled brown with no epaulets. To us, it looks more like a sparrow than a relative of the red-winged blackbird. In this species the female has no need for flash, explains Rubega. She is looking for a space for youngsters and to have food. She’s looking for signs of vigorousness in a mate, proof he can hold the territory for her ”” the brighter the epaulets the healthier the male.

An iridescent bird swoops low in front of us. “That’s a barn swallow and it is fabulous,” says Rubega. “Everybody who does not care for bugs in their eyes and ears should be fans of swallows.”

We are moving toward the barns and the Horsebarn Hill Arena parking lot, because a few days prior I had seen what I thought was a kildeer on the tarmac there and a bluebird on the telephone wires nearby. Neither would be unusual, says Rubega. Why would a kildeer crouch at the curb of a parking lot that’s surrounded by grassy fields? It likes ground that’s sufficiently disturbed, says Rubega. This plover species has bold black neck bands that serve as what is called disruptive coloration, a trait that breaks up an animal’s coloring so that a predator’s eye doesn’t perceive it as an actual animal. “So they don’t dislike edges of paving or places that used to be paved and are now all broken up.”

Though she confirms the ID by looking at a picture on my phone, the kildeer itself does not appear for us. Which is too bad, because it is nesting season now and kildeer are known for dramatic “broken wing displays” in which they pretend to be easy prey to lure predators away from their nests. It’s a display Rubega seeks out to show appreciative students.

Meanwhile, however, an accomodating bluebird has landed on a telephone wire just above us. Amid describing the “exceedingly pleasing nature” of the bird’s red and blue hues, Rubega interrupts herself with an exclamation of “Oh, look ”” pigeons!” She follows this with a laugh and then a serious declaration: “People should not disdain pigeons. Pigeons are a fine example of what I mean when I say birds are everywhere. People overlook them because they’re common, but there are always really interesting things going on in the bird world and even pigeons are fascinating.”

“Get some tickproof clothing and get out there. There are plenty of hazards to staying indoors!”

For instance, “they are not just sitting on the building, they can hear it,” says Rubega of the flock that has just landed on a silo.

Pigeons hear infrasound, too low-pitched for humans to hear (the opposite of high-pitched ultrasound), and that includes the sound of air hitting buildings. These wayfinding superheroes also use magnetic fields and celestial landmarks like stars to navigate. And, like all birds, they have extra cones in their retinas so they see colors that humans cannot.

“People look at the sky and try to imagine themselves as a bird, right” says Rubega. “You imagine birds seeing the world the way you would if you were up there. They are completely not experiencing the world the way you are; the world looks completely different to them.” Rubega pauses, then lets her binoculars drop and says, “If you want to contemplate your existence, to just come down here and look at pigeons would be enough. But UConn is blessed with so many good bird spots.”

This is a direct result, she says, of getting its start as a land grant University. There remain swaths of grassland habitat and open space you might otherwise not have. As she says this, we are walking toward the cow barns with fields full of starlings and grackles to our left and barns alive with house sparrows and barn swallows to our right. There’s a nesting box along the fenceline here that’s home to a family of kestrels, smallish hawks. The University lets a local enthusiast install boxes for the endangered bird.

“Kestrels are a pretty good farm bird,” says Rubega, “They eat nothing except for small rodents and insects ”” and what else could a farmer possibly want a bird to do?”

She spies one atop the tallest branch of the tallest tree in the field, just below the ridgeline “just sitting up there waiting for a mouse or a big juicy grasshopper to go by.” Before we’ve had a chance to train our binoculars on the kestrel, Rubega turns our attention further skyward. “And here comes a great blue; he’s big and molting ”” see the break in the wing,” she says of a great blue heron who looks like little more than a far-off silhouette to our untrained eyes.

Horsebarn Hill is “the big Kahuna” of birding on Storrs campus, says Rubega. Besides the barn swallows, bluebird, kestrel, pigeons, and kildeer shown here, you easily can find various warblers, starlings, sparrows, cardinals, robins, jays, wrens, finches, doves, crows, grackles, snipe, flickers, catbirds, phoebes, nuthatches, hawks, and more.

Mirror Lake

The heron may well have been on its way to or from Mirror Lake, where you can often see them statue-still amid the cattails, oblivious to the the cruising mallard ducks, patiently waiting to spear a trout or carp.

A successful reclamation project that included digging out invasive plants and adding fountains for aeration has brought the cattails back and, along with them, some beautiful birds and insects. “It provides a really nice band of habitat for the sort of things that need a little bit of vegetative intensity to build a nest and not be right out where predators can see them.” This includes red-winged blackbirds, sweet-singing Carolina wrens, and of course ducks.

“This is a very birdy place. Mirror Lake is well worth a circuit at any given time,” says Rubega, watching a duck preen. “Ducks spend a good deal of their day preening to stay waterproof. Birds are always dry, even though they’re touching the water, they’re dry. If you see a water bird that’s wet it’s about to be dead,” she says in the matter-of-fact way of a scientist.

Elegant gray-and-white birds are performing aerial gymnastics above the lake as we talk about ducks. They are phoebes catching bugs right off the surface of the lake, Rubega tells us, pointing out “a pile of them” in a tree behind us. These are juveniles trying to get fed, she says. “Listen. It’s ”˜feed me-feed me-feed me.’ Not unlike college students, they’re trying to extract as many resources from their parents as they can before they get kicked to the curb for good. It’s a stable phenomenon in the animal world.”

Just then we get a glimpse of a bird that makes everything else we’ve seen, even the bluebird, pale in comparison. “That is a beautiful cedar waxwing,” says Rubega. “They are the most incredible looking birds. They are so freaking gorgeous.” Indeed the red, yellow, and green colors and the Zorro-style eye mask are stunning. “The subtlety of their color scheme, if you could reproduce that in textiles you would be so rich,” says Rubega.

Incredibly, this bird is not uncommon and is here year-round. “They’re an excellent example of the kind of bird that once you get students to actually look at the bird, they get an eyeful, put down their binoculars, and say, ”˜That bird was not here all along.’ But, yes, it is that fancy and, yes, it has been here your whole life!”

The first year Rubega did the Twitter assignment, a student turned in what is perhaps still her favorite post: “Holden Caufield once asked where the ducks go in winter and never really got his answer. He should have walked by Mirror Lake at UConn today.”

“I looked at that and said to myself, ”˜There it is ”” a liberal arts education in 140 characters,’” she says.

Rubega Wisdom

At Mirror Lake: the plantings around the edge are habitat for the sort of bugs that attract birds this time of year. Nobody’s eating fruit right now because they need protein for their babies to grow.

Watching a pileated woodpecker: You can put it on your shit list, because it just pooped right in front of you! Birders keep lists of everything.

On blue jay behavior: I actually love me a blue jay. They’re a good strong predator. They’re just making a living and the fact that they’re good at it gets attention.

On “silly” woodpeckers pecking at an aluminum house: He knows exactly what he’s doing. He’s advertising for a girlfriend. He’s found a really good resonator and he’s making use of it.

Mirror Lake is rich bird habitat any time of day, any time of year, says Rubega. In addition to the phoebe, mallard, cedar waxwing, goldfinch, and great blue heron shown here, a quick lunchtime stroll can turn up black-capped chickadees, nuthatches, tufted titmice, egrets, herons, all manner of ducks, geese, or gulls, and even a passing-through osprey.

The Platforms

It is another early morning for civilians and we are traipsing through knee-high grass and weeds, serious tick territory, behind Discovery Drive. This is no barrier to Rubega’s birding. “Get some tickproof clothing and get out there,” she says. “There are plenty of hazards to staying indoors!”

This territory is much less daunting at other times of year, but even now in early summer our trek proves worthwhile when we come to the first of two wooden platforms built over wetlands and see, within seconds, a pileated woodpecker. This is the real-life Woody Woodpecker, enormous and brilliant.

“I think the pileateds are very exciting,” says Rubega. “My students were beside themselves when we came out here and there was a pair of them actively courting ”” displaying and calling.”

These are the moments Rubega hopes will jostle students out of what she calls “the BBC effect.”

While televison has gotten people excited about wildlife, Rubega believes that the proliferation of animal shows has had a negative impact as well. “People love to watch the type of show with the British announcer intoning while the eagle takes down some big piece of prey and it does create interest in wildlife,” says Rubega. “But it also gives people the idea that natural history is taking place somewhere else, in some exotic place not near you. So for a student who goes back and forth from classes all day to come out to a place like this and see an enormous woodpecker with a bright red head and this specatacular black-and-white pattern on its body drilling big holes in a tree? It blows their mind because it’s not somewhere else. It’s right here!”

Deep in the woods behind Discovery Drive lies a pair of wooden platforms protruding into wetlands that are home to the barred owls, red-bellied woodpeckers, red-winged blackbirds, and northern flickers, among many others.

The Loop: W Lot and the Cemetery

A short walk from the W Parking Lot we’re ensconced in woods and the baritone sounds of bullfrogs. Rubega often takes students on a loop that begins here and winds behind Charter Oak Apartments, past the cemetery and back to the lot. We’ve been stalking what turns out to be a wild turkey with two chicks. Two doesn’t seem like much of a brood.

There’s a lot of mortality in the early life of chicks, says Rubega, in part due to the number of feral and nonferal cats here. It’s a sore subject for this ornithologist, who says that nonferal cats in Connecticut are decimating bird populations. And do not make the mistake of suggesting that it’s a natural process.

“People argue that the cat is a natural predator. No. A natural predator is one who, when it eats too many of the prey base, its population naturally gets cut back because there’s not enough food to go around. So there’s a built-in control valve to keep the predator from driving the prey all the way to extinction. When your cat goes out and kills 10 birds a week and then comes home and gets fed an artificial diet and gets taken to the vet, there’s no control valve. If I were Emperor of the World, I’m not sure there would be housecats, but there certainly wouldn’t be any outdoors.”

We are at the edge of the woods now and bird noises are plentiful. Birders seek edges because it’s easier to see birds where habitat changes. Right now Rubega says she can make out the sounds of crows, blue jays (“the rusty hinge”), mourning doves, catbirds, redwings, chipping sparrows, a distant northern flicker, catbirds, downy woodpeckers, a red-bellied woodpecker, and, far in the distance, robins.

A nearby bird seems to be making a number of sounds in a row.

“That would be a mockingbird,” says Rubega. Every semester she lectures about mimicry in birds and mockingbirds are excellent mimics. She tells us about a lecture in which she talked about hearing a mockingbird that was on territory in a campus parking lot. The bird had car alarms and cell phone tones in its repertoire. “The whole point for a male mockingbird is to pick up every novel sound that it can because female mockingbirds find novelty and size of repertoire sexy.”

One of her students was so taken with this information that as soon as class was over, he went down to the lot and tested a theory.

“Within an hour and half of class he had posted: ”˜Taught a mockingbird the Jet Whistle in around 8 minutes.’ He stood in the parking lot making “the Jet Whistle” until the bird started making it back to him.

A student I had not given an assignment to went and did an experiment on his own and then reported it to the world at large ”” in his own backyard!

And I said to myself, ”˜My work here is done.’”

Want to join fellow alums and associate professor Morgan Tingley in May 2018 for a “Birding in the foothills of the Himalayas” trip? Find out more at uconnalumni.com/birding.

“One thing about the Lot W fields,” says Rubega, “is that a lot of students walk through here and a lot of commuters park in this lot. It’s a place where you can get out of your car and explore for 15 minutes and get back in your car and have gotten some birding into your day.” Indeed, within a few minutes of stepping out of our car, we’d seen a chimney swift and a red-tailed hawk.

Rubega calls this a classic campus birding spot. “Even if you have just five minutes during lunchtime,” she says, “you can go up to the graveyard and see who’s around.” On any given day that could be turkeys, flickers, robins, swifts, or bluebirds. In the winters, says Rubega, this is the spot to see bluebirds.

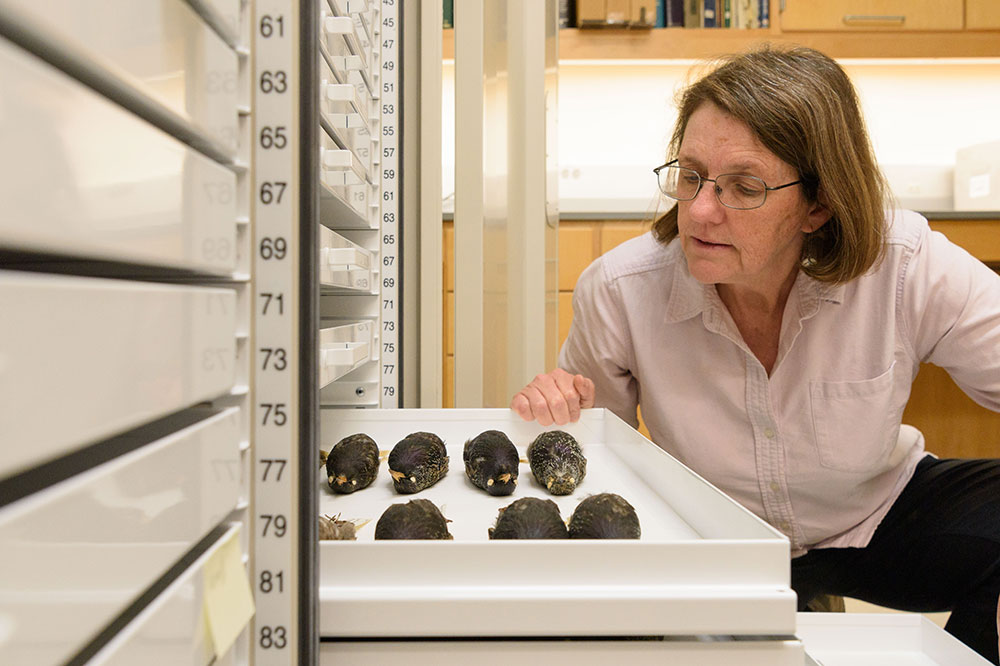

The stuffed starlings Rubega is looking at here in the Biodiversity Research Collections Room in Storrs were collected in the 1800s when starlings were first introduced to this country from Europe. Every starling in this country descends from 100 starlings that were released in New York City’s Central Park in 1890 and 1891. Within a few years, the prolific bird, which often raises two to three broods of three to six young every year, spread widely along the Connecticut River valley. By 1921 they were found from Maine and New Hampshire to Ohio and West Virginia.

The stuffed starlings Rubega is looking at here in the Biodiversity Research Collections Room in Storrs were collected in the 1800s when starlings were first introduced to this country from Europe. Every starling in this country descends from 100 starlings that were released in New York City’s Central Park in 1890 and 1891. Within a few years, the prolific bird, which often raises two to three broods of three to six young every year, spread widely along the Connecticut River valley. By 1921 they were found from Maine and New Hampshire to Ohio and West Virginia.

Leave a Reply